Applied Research Dissertation

Presented and defended by

June 5, 2020

The Expansion Analysis of Penfolds in China

MBA << Wine Marketing and Management>>

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my tutor, Gérard Spatafora, who offered constructive suggestion to my dissertation and has been very patient. I cannot achieve this dissertation without him.

Also, I appreciate all participants and respondents of the interviews and questionnaires who spent their valuable time in offering data.

Abstract

This research aims to describe and analyse Chinese wine industry, including market trend, consumer behaviour and demands, to study the expansion strategy of Penfolds, to identify why the expansion strategy works and how it works, and to identify whether or not Penfolds’ strategies can be applied to a new brand coming from Australia and other countries. This research has two parts: 1) first part uses literature, secondary data and interview to study the expansion strategy of Penfolds; 2) second part adopts literature and questionnaires to examine whether or not Penfolds’ strategy can be applied to other wine brands.

The research adopts the following research methodologies: realism, case study, mixed methods, cross-sectional time horizon, interviews, and questionnaires as data collection methods. It collects both primary and secondary data to analyse the Chinese wine market and expansion of Penfolds. It uses case study to generate in-depth findings. Also, it uses both interviews to collect qualitative data and questionnaires to gather quantitative data.

This research finds that using integration of standardisation and adaptation in market mix is an effective tool to penetrate into Chinese market. This also is the major reason that Penfolds successes in China. High-end wine brands should adopt export as entry mode. These brands should directly control its wholesales and offers these wholesales a certain level of autonomy allowing them to design and implement localised strategy. In term of Uppsala model, these brands should collect internationalisation experience and develop business networks. They should develop business networks including wholesalers and online retailers and then increase their involvement and commitment in China. More importantly, these brands should implement integration of standardisation and adaptation strategy in their market mix.

1.4 Economic and Cultural Aspect of the Research Phenomenon

1.6 Justification of the Layout

2.1 Motives of Internationalisation

2.2.1 Hofstede Cultural Dimensions

2.2.2 Chinese Consumption Culture

2.4 Entry Strategy and Entry Mode

2.6 Standardisation / Adaptation

2.8 Consumer Buying Decision Process

3.3 Research Strategy: Case Study and Survey

4.1.1 Secondary Data Analysis of Expansion Strategy of Penfolds

5.1 Chinese high-end Wine Consumption

5.2 What is the penetration strategy of Penfolds to expand into China?

5.3 Why and How effective is the penetration strategy?

5.4 What are recommendations for other wine brands from Australia or other countries?

6.2 Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Context

A recent event motivates the wine marketers to pay more attention to China. With outbreak of COVID-19, global economy is expected to experience recession, much more serious than 2008-09 Financial crisis. It is projected to decrease by 4.9% in 2020, according to IMF’s forecast in June 2020 (IMF, 2020). During 08-09 Financial crisis, Australian wine production dropped sharply (Statista, 2020). Thus, the economic recession caused by COVID-19 strongly can heavily hit wine industry. The economic recession in developed countries is projected to reduce demands for high-end wine. However, China has controlled the pandemic disease and started to recover its economy, when many developed countries are facing challenges to contain the pandemic disease. China re-started business operations and economic function in March. Thus, Penfolds and other brands must increase their commitment and involvement in Chinese market.

With the rise of middle class in China, wine consumption has been continuously growing. In 2018, the wine consumption of China reached 17.6 billion. Even through the figure dropped comparing to 19.3 billion in 2019, the Chinese market is highly promising, which made China as the fifth largest wine consumption country (Blazyte, 2020). The health awareness of Chinese people is growing, whereas it is not strong as much as that of Australian and European people. There is no alcohol rehab centre in China and Chinese people do not consider addiction to alcohol as a disorder.

Figure 1: Wine Consumption in China 2000-2018 (Source from: Statista, 2018)

Penfolds operated a successful expansion to China, known as ‘Ben fu’ in Chinese. It literately means ‘hitting to richness’ or ‘route to become rich’ in Mandarin. It is safe to say that Penfolds developed a successful brand image. To be noticed, Chinese people have less knowledge about the wine quality like European people do. They only experienced wine for less than 30 years. Therefore, Chinese people tend to be highly concerned about brand image when they make purchase decisions on wine.

Currently, Penfolds focuses on direct marketing by e-commerce. Partnering with Chinese online retailing giants such as Taobao (Alibaba) allows the company to effectively distribute its products. More importantly, it also has penetrated offline distributors by partnering with high-end store chains such as Ole.

1.1.1 Penfolds

Penfolds is an Australian wine manufacturer which was built in Adelaide in 1844 by Christopher Rawson Penfold. Penfolds is rewarded the World’s Most Admired Wine Brand 2019 (Waterworth, 2019). The brand has been maintaining an excellent consistency in quality and style throughout its product lines (Waterworth, 2019).

Penfolds has a long and glorious history. Christopher Rawson Penfolds was an English physician who immigrated to Australia when he was 33 years old (Penfolds, 2020). He recognised the medical uses of wine and manufactured fortified wines for patients. With the increasing demands, the Penfold winery was officially found in 1844. Penfolds’ wife, Mary started experiments and found new methods to produce wine. After her retirement, this daughter Georgina and son-in-law took the duty of running the business. In 1903, Penfolds produced 450,000 litres of wine and became the largest winery in Adelaide (Penfolds, 2020). Between the 1940s and 1950s, Penfolds shifted its strategy to table wines to adapt to changing demands. In the 1960s, it launched many red wine product lines including Bin 389, Bin 707, Bin 28, and Bin 128 (Penfolds, 2020).

The ownership of Penfolds has been changing with its growth. The Penfolds winery had been a family business until 1962 when it became public (Penfolds, 2020). The Penfold family held a controlling interest between 1962 and 1976 (Penfolds, 2020). In 1976, Tooth and Co, acquired the control of Penfolds and was acquired by the Adelaide Steamship Company Group in 1982. After 8 years, SA Brewing acquired the Adelaide Steamship’s wineries. It divided into three organisations and one of them was known as Southcorp Wines which run the wine business. Foster’s Group acquired Southcorp Wines in 2005 and demerged its wine business in 2011 (Penfolds, 2020). Its wine operations became Treasury Wine Estates (TWE) which was sold at the Australian Securities Exchange. Thus, Penfolds has been owned by TWE and managing two wineries since 2011.

TWE has large scale of economies which are beneficial to the growth of Penfolds. According to TWE Global (2020), TWE has 3,500 employees, operates in 100 countries, focuses on 4 regions (Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, Europe, and Asia), and owns 13,000 hectares of vineyards. It collected AU$ 2,883.0 million revenue and AU$1,222.2 million gross profit and realised AU$ 419.5 net profit in 2019 (TWE Global, 2020).

1.2 Research significance

This research is significant that has managerial contributions. Chinese wine consumption is increasing, which is a great opportunity for all wine brands. On the opposite of China, the alcohol consumption of many European countries has been sharply declining. For example, wine consumption in France plunged down to 27 million hectolitres in 2017, decreased by 21.7% comparing to 2000. Therefore, it is prominent for Penfolds and all wine manufactures to grasp the opportunity in China. The findings of this research can analyse successful expansion of Penfolds and make recommendations for other high-end brands. The research plans to describe and analyse Chinese wine industry, including consumer behaviour and demands, which is prominent to foreign wine companies. The results of the research can help wine brands to understand Chinese buyers’ consumption habits in high-end wine sectors and take lessons from Penfolds’ successful expansion.

Furthermore, the research has significantly academic contributions. Academic studies on wine brands’ expansion in China are rare. Many studies clearly identified entry mode (Cunningham, 1986), choice of entry mode (Dunning, 1979), standardisation / adaptation strategy (Melewar and Vemmervik, 2004), and consumer buying process (Qazzafi, 2019). Meanwhile, some studies recognise strong impacts of culture on international expansion (Darley et al, 2013; Ekerete, 2001; and Jiang and Wei, 2012). However, none of these researches apply the knowledge into the wine industry and wine brand’s expansion in China. Thus, there is the research gap that studying international expansion of high-end wine brand into China. This research attempts to cover the research gap by applying Uppsala model, OLI model, and standardisation/adaptation to study the case of Penfolds. Additionally, the research analyses the impact of Chinese culture on high-end wine consumptions based on Hofstede’s national culture dimensions. It can contribute to the understandings of Chinese consumers’ wine consumption habits in academic field.

1.3 Research Aims

This research aims to describe and analyse Chinese wine industry, including consumer behaviour and demands, to study the expansion strategy of Penfolds, to identify why the expansion strategy works and how it works, and to study how other brands to take lessons from Penfolds’ strategies to expand into China. The purpose of this research is to analyse how and why Penfolds’ expansion in China is successful, study Chinese consumers’ needs and wants, and make recommendations to other high-end wine brands’ expansion in China. To study the expansion strategy, the research evaluates Penfolds’ entry mode and marketing mix.

In this sense, this research has two parts: 1) first part uses literature, secondary data and interview to study the expansion strategy of Penfolds; 2) second part adopts literature and questionnaires to examine whether or not Penfolds’ strategy can be applied to other wine brands.

Research objectives

1. To review literature to build a theoretical framework for the research

2. To collect secondary and primary data related with Chinese wine market and Penfolds’ expansion

3. To how other wine brands to take lessons from Penfolds’ strategy to expand into China.

4. To discuss findings of this research with literature to generate conclusions and recommendations for other wine brands

Research Question

1. What is the penetration strategy of Penfolds to expand into China?

2. Why and How effective is the penetration strategy?

3. What are recommendations for other wine brands from Australia or other countries?

1.4 Economic and Cultural Aspect of the Research Phenomenon

The role of China in global economy is becoming increasingly more important. The country reached $14.140 trillion nominal GDP in 2019 and ranked the second largest economy by GDP after the US (Gill, 2020). After the bust of COVID-19, the China’s GDP is estimated to increase 1.0% whereas the US’s GDP is forested to drop 5.9% (Gill, 2020). Furthermore, China has become the largest manufacturer around the world and played an important role in global value chain. It held 28.4% of global manufacturing output, followed by the US (16.6%) (Richter, 2020). As a strong emerging market, the demand in China has been continuously growing. China is an important driver of global economy. Thus, for global economic aspect, it is important to study Chinese wine market.

Moreover, the Chinese wine market is strongly related with Chinese culture. Due to cultural divergence, Chinese people’s consumption habits and buying behaviour are different with people’s Western countries (Darley et al, 2013). Thus, studying Chinese wine market must consider Chinese culture.

1.5 Research Methodology

To accomplish the research aim and objectives, the research has two parts. The first part adopts qualitative analysis in accordance with interpretivism philosophy. It uses case study as research strategy to study the expansion of Penfolds in China by analysing secondary data. Then, it designs semi-structured interviews based on the result of the analysis to collect primary analysis to analyse Penfolds and Chinese consumers’ purchasing habits, preferences, and needs. The second part implements quantitative analysis in alignment with positivism philosophy. It designs questionnaires based the results of secondary data and interviews analysis. It uses questionnaires to study whether or not Penfolds’ marketing mix is applicable to other high-end wine brands. Moreover, the research adopts deductive approach that uses existing knowledge to make explanations.

1.6 Justification of the Layout

The research starts with the Chapter 1, ‘Introduction’ to justify the research significance, aims and purposes and briefly introduce research methodology and research plan. Based on deductive approach, the research plans to study Penfolds and Chinese wine market based on existing theories. Thus, it critically reviews literature in the Chapter 2, ‘Literature Review’. The Chapter 3, ‘Research Methodology’ justifies the choices of research methodologies to explain how and why the research objectives will be approached and accomplished. The Chapter 4, ‘Data Analysis’ analyses data in two parts. The first part analyses qualitative data including secondary data and primary data from the interview. The second part is designed to analyse quantitative data from the questionnaires. The Chapter 5, ‘Discussion’ discusses the results of the data analysis with literature to answer the research questions. Additionally, the latest chapter, ‘Conclusion’ summarises all findings in respect to all research questions, analyses the research’s limitations, and make recommendations for further research.

1.7 Research Plan

The research plans to start with literature review to evaluate existing knowledge. Based on the existing knowledge, it analyses Penfolds’ expansion by secondary data. Then, it designs interviews based on the literature review and secondary data analysis. It analyses interviews to develop questionnaires and collect quantitative data. By questionnaires, the research can generate universals for all high-end foreign wine brands to penetrate into China.

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Motives of Internationalisation

The motives of internationalisation can be categorised into four groups: 1) market seeking, 2) resource seeking, 3) efficiency seeking and 4) strategic resource seeking (Dunning, 1993). Dunning (2000) adds network seeking motivates describing those international companies which realise the importance of networks as a prominent component of internationalisation. His theory suggests that internationalisation is motivated by opportunities rather than threats. Furthermore, Francis and Collins-Dodd (2000) highlight that internationalisation is motivated by the increase in sales. This study also proves the significance of strategic alliances patterns to enhance foreign market performance. This means that seeking networks is an important factor.

Market Seekers

Market seekers refer to those companies which realise the importance of reaching certain target markets in overseas and the significance of a direct presence in foreign market for reaching target customers. They invest in a certain country to provide products. In Dunning (1993)’s theory, there are some reasons for companies to become a market seeker. Companies invest in foreign market in order to facilitate or exploit new markets with the purpose of increasing their market size and growing sales. In this process, these companies tend to use adaptation strategy to meet local demands. Meanwhile, these companies may be motivated by its competitors’ international expansion. They develop their physical presence on leading markets in which have their competitors. Furthermore, some companies’ home market is limited, highly competitive, or saturated that cannot sustain sufficient revenue (Hollenstein, 2005). Therefore, these companies seek opportunities in foreign markets in which has less competition but abundant target customers. Internal and external environment analysis is one of the major considerations of a company’s internationalisation. A company trends to believe that it can gain competitive advantages in foreign market and thus launches internationalisation.

Resource Seekers

In Dunning (1993)’s theory, resource seekers mean those companies seeking resources by investing in foreign markets. Those companies tend to gain resources including natural resources, low cost labours, or unique skills and capabilities by collaboration with a business partner.

Efficiency Seekers

Efficiency seekers expect to develop efficiency to gain benefits. Their expectations include developing economies of scale to reduce and reliving risks by diversifications (Dunning, 2000). Furthermore, a higher efficiency can retrieve from differences in cultures, institutions and economic systems.

Strategic Resource Seekers

This group of companies seek mostly seek intangible resources associated with technologies and core capabilities (Dunning, 1993). In resource-based view, a company’s competitive advantages are developed from rare or unique resources and capabilities (Boermans and Roselfsema, 2012). Strategic resource seekers therefore demand unique resources and capabilities in foreign markets, including patents, knowledge, employees’ skills, and strategic supplies which are strategically important for development.

Network Seekers

Networking is an important aspect of international entrepreneurial culture (Dimitratos and Plakoyiannaki, 2003). The network orientation shows the extent of which a company participate in alliances and collaborative values. In alignment with resource-based review, companies need to acquire unique resources and capabilities to develop competitive advantages. Developing networks in overseas allows companies to gain those desirable resources and capabilities (Chen, Chen and Ku, 2004). Chen and Huang (2004) highlight that existing networks are unable to empower strategic goals of a company. Therefore, the company chooses to develop international networks by internationalisation. Companies can gain critical resources and capabilities by alliances and networks to develop their competitive advantages (Lavie, 2006).

2.2 Culture Theory

Culture refers to a group of people’s collective thinking in a society. It shows beliefs, customs, and attitudes of a different group of people (Baack, Harris and Bacck, 2011). Culture causes the differences in attitudes, perceptions, tastes, preferences, and values (Suh and Kwon, 2002).

Culture difference acts an important role in internationalisation process (Hutzschenreuter, Voll and Verbeke, 2011). They find that high level of cultural distance tends to have negative influences on international expansion due to adjustment costs. Culture difference is a high barrier to a company’s internationalisation, causing misunderstanding, conflicts, and ineffective marketing communications. They further explain that management of subsidiaries in host country with strong culture differences faces the difficulties and complexities of rising environmental and internal governance.

Many scholars agree that high culture difference negatively affects international expansion (Darley et al, 2013; Ekerete, 2001; Jiang and Wei, 2012 and Peprah, Ocansey and Mintah, 2017). Culture has impacts on marketing activities, free trade policies, branding, localisation and standardisation decisions, international negotiation, business relationship, consumer behaviour as well as global marketing (Darley et al, 2013). These however are important tasks for a company’s internationalisation. Cultural differences cause barriers to international marketing communication by language, religions and ethnic values (Ekerete, 2001). Peprah, Ocansey and Mintah (2017) highlight that culture has significant impacts on global marketing strategies. They explain that culture differences can cause misunderstanding and misinterpretations in marketing communications. International marketers need to pay heavy attention to cross-cultural issues. MNC tends to adopt localisation strategy to develop international branding and advertising because of cultural differences (Jiang and Wei, 2012). The study also underlines the increasing phenomenon that international companies are more concerned about local cultures. Jawal (2014) argue that companies need to attach importance to cultural influence on their products when they conduct international expansion. A study focusing on the impact of culture negotiating on international market proves that cultural barriers including language, religions, social environment, legal and political environment, and technologies act important role in the performance of companies’ internationalisation (Antunes et al., 2013). Kaur and Chawla (2016) illustrate that companies have to acquire cultural knowledge of specific group to develop marketing strategies for global penetration of a product. This study reveals that culture has impacts on production promotion activities in different foreign markets because the divergences in customs, norms, and cultural values. Peprah, Ocansey and Mintah (2017) further explain that culture causes obstacle to communication and divergences in consumer behaviour, buying pattern, lifestyle and belief, and different religions have influences on consumer behaviour. Terpstra and Sarathy (2000) argue with this explanation and find the evidence supporting that divergences in technological, social and legal environment can differences in customer behaviour. Given that far-reaching and deep influences of culture difference, Rao-Nicholson and Khan (2016) underlines the necessity of studying culture and developing cultural competencies and knowledge before globalisation process. Because of cultural differences, MNCs are unable to use standardisation strategy (Jiang and Wei, 2012).

Cultural distance means the differences in value, attitudes, perceptions, and communication styles deeply rooted in culture (Hofstede, 1980). Converged with the impact of cultural difference, many scholars prove that cultural distance has impacts on corporate internationalisation (Beguelsdijk et al., 2017). Scholars explains that the broad concept of cultural distance includes geographic differences (Elden and Miller, 2004), economic policy and system (Ghemawat, 2001), and institutional differences and language differences (Dow and Karunaratna, 2006). These distances cause a highly different external environment and difficulties for international companies. Therefore, cultural distance has strong impacts on a company’s internationalisation (Beguelsdijk et al., 2017).

2.2.1 Hofstede Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede (2001) revisits its national cultural dimensions to measure national culture differences and there are six cultural dimensions including power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and indulgence. Power distance measures the degree to which people of a society tolerate inequal distribution of power (Hofstede, 2001). Individualism addresses the extent to which people of a society are independent among others (Hofstede, 2001). Uncertainty avoidance measures how people of a society define success and refers to the emotion role of men and women (Hofstede, 1991). Long-term orientation examines how people of a society view future and the extent to which these people concern the present future (Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov, 2010). Indulgence evaluates the degree to which members of a society to suppress their desires and impulses (Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov, 2010).

As figure 2 shows, the Australian and Chinese culture is diverged in power distance, individualism, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and indulgence. Chinese people have stronger tolerance to unequal distribution of power such as powerful people’s privilege, who therefore show more respect to people with greater power and older people (Emery and Tian, 2010). Meanwhile, with low level of individualism, Chinese people are deeply involved into others and prefer strong relationship with others (Moser et al., 2011). With Confucianism, Chinese people advocate harmony and avoid conflicts with others. They heavily rely on Guanxi (connections and relationships) in their life. Face-saving is important for them to reserve Guanxi (Lee and Dawes, 2006). Thus, they use intermediates and send ambiguous messages in communication to prevent direct rejection and dispute. With a high score on masculinity and a low score indulgence, Chinese people restrain their desires and impulses and are inclined to cynicism and pessimism (Bluszcz and Quan, 2016). They are restrained by social norms and they perceive that indulging themselves is wrong. With a low score on uncertainty avoidance, Chinese people have greater tolerance to uncertainties, and they rely on relationship rather than rules to reduce uncertainties (Moser et al., 2011). In term of long-term orientation, Chinese people stand at the viewpoint that truth relies heavily on situation, context, and time (Moser et al., 2011). They have strong capability to adapt traditions to new circumstances, a strong preference to saving, investment, and thriftiness.

Figure 2: Hofstede Culture Dimension: Australia Versus China

(Source from: Hofstede-Insights, 2020)

2.2.2 Chinese Consumption Culture

Liu et al. (2011) study the cultural influences on Chinese consumers’ intentions to buy Australian products based a large sample. This study finds that favourable perspectives of ingroup members significantly and positively affect Chinese buyers’ purchase intentions. Ingroup members can be viewed as a social circular including family, relatives, friends, and co-workers. This finding aligns with the argument that people in highly collectivistic culture are highly motivated to follow or imitate their important others or the reference group (Liu et al., 2011). The ingroup is one of core characteristics of collectivistic cultures (Zhang and Khare, 2009). Generally, Chinese people have preference to imported goods from Western countries and consider these goods as better, representation of higher social status, and premium quality and performance (Liu et al., 2011). Zhao (1998) highlights that Chinese buyers carefully evaluate imported products before making purchase decision besides the higher status of imported products. They compare imported products with counterparts made in China because imported products sell at higher prices. Chinese consumers consider price, which is an important factor affecting Chinese purchasing decisions (Liu et al., 2011). The subjective perspective of price acts a dual role in Chinese consumers’ perception of a product (Gong, 2003). To be specific, Chinese consumers perceive that a lower price normally implies a lower quality, whereas a higher price conflicts with Chinese mainstream value of thrift (Liu et al., 2011). Even though Chinese respondents indicate that they prefer local brands, their actual purchase behaviour shows that they prefer foreign brands (Kwok et al., 2006).

Another purchase habit of Chinese consumers is to purchase for gift-giving. Chinese people prefer to keep close tie with their family, relatives, and friends (Xiao and Kim, 2009). In accordance with collectivism, Guanxi (connections and relationships) is important for Chinese people in their life. Therefore, they have the habit of giving gifts on Chinese traditional festivals to maintain Guanxi. Mei (2016) study the gift-giving culture in China. The study shows that gift-giving still acts a prominent role in generating and fostering relationships with people in China even though Chinese people are becoming more individualistic. They are pragmatic in interpersonal communication and have the pattern of showing their feelings, thoughts, and gratitude by materials such as gifts. Under collectivism and Confucianism, Chinese people value Guanxi and pursue harmony. In this sense, they advocate a conflict-free and group-oriented system of human relationship (Mei, 2016). Thus, they give gifts to others to maintain or foster relationship.

2.3 Uppsala Model

Uppsala internationalisation model realises the significant impacts of culture and elaborates a learning process for international companies to increase their cultural and market knowledge. Johanson and Vahlne (2009) revisit the model to adapt to the change in market environment since 1977. The model effectively interprets a company’s internationalisation process. Based on the 1977’s model, they propose a new model as figure 1 shows. The new model still focuses on market knowledge and adds the intention of network position. The model highlights the importance of knowledge and networks. This means that foreign companies need to develop business networks in host countries and rely on the networks to grow its presence, activities and commitment in these countries. By developing relationship commitment, an MNC can gain more knowledge from partnership which in return contributes to knowledge transferring. Knowledge acts an important role in internationalisation of a company enabling the company to overcome cultural and regulatory barriers. The new model is consistent with knowledge transferring between a foreign company and its business network in host country. In other words, it argues that importance of business network and relationship with local partners in a MNC’s international expansion. The MNC’s commitment to a foreign market is related with the extent of its business network and relationship.

Figure 3: Uppsala Internationalisation Model

(Johanson and Vahlne, 2009)

Furthermore, Uppsala model highlights a learning curve of a company’s internationalisation. It suggests that a company increases knowledge for global expansion during its internationalisation process. In this theory, a company expands into a country which is geographically and culturally close to its home market and then gradually expand into those markets which are geographically and culturally far away its home market. The model uses the concept of culture distance to explain the learning curve. Companies grow their knowledge and competencies to relieve the impacts of cultural distance. Thus, the older Uppsala model focuses on market knowledge and suggests a company to decides its commitment and activities in host country based on its market knowledge as figure 2 shows.

Figure 4: Upsala Model

(Johanson and Vahlne, 1977)

2.4 Entry Strategy and Entry Mode

Market entry strategy has strong influences on a MNC’s performance of international expansion. Cunningham (1986) illustrate that there are five strategies adopted by companies to expand into new foreign markets including 1) technical innovation, 2) product adaptation strategy, 3) risks avoidance strategy, 4) pricing penetration and 5) total adaptation strategy. The choice of entry mode is related with a MNC’s performance in host country. Those entry modes available for MNCs include direct exports, indirect exports, licensing, franchising, turnkey projects, Wholly owned Subsidiaries (WOS), joint venture, and strategic alliance.

2.5 OLI Model

OLI Model can be used by an MNC to choose its entry mode. Dunning (1979) proposes three important dimensions used to determine the choice of entry model.

Ownership advantages

It means competitive advantages of an MNC enabling it to engage in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). With stronger competitive advantages, an MNC is more likely to develop manufacturing facilities in a foreign market (Dunning, 2000).

Location advantages

These advantages mean locational attractions for an MNC to improve its value-adding activities. The MNC desires natural, immobile resources to develop its competitive advantages. If these resources can sustain its competitive advantages, it tend to involve in FDI.

Internalisation advantages

These advantages mean that an MNC has advantage of organising the creation and exploitation of their core capabilities. If an MNC has advantage to operate manufacturing tasks by itself, it tends to use FDI.

2.6 Standardisation / Adaptation

Culture acts an important role in determining standardisation and adaptation approach (Heerden and Barter, 2008). Standardisation and adaptation are two contrasting strategy for a company’s international expansion.

Standardisation highlights the trend of globalisation and homogeneity of culture and customer demands. Melewar and Vemmervik (2004) highlight that global market is moving toward convergence allowing MNCs to provide standardised products. Meanwhile, Herbig (1998) highlights that global culture is converging that results in a similar global demand. Standardisation allows MNCs to increase economies of scale and reduce costs and ensure global consistency and coherency. Viswanathan and Dickson (2007) illustrate that standardisation approach is beneficial for an MNC to ensure its product quality and global branding.

On the other hand, adaptation highlights the significant impacts of culture making standardisation less effective (Haron, 2016). Due to cultural differences, consumer behaviours are varied. As the result, standardisation is unable to help companies to meet local demands (Melewar and Vemmervik, 2004). Adaptation requires companies to have in-depth marketing knowledge and high customised costs, whereas it allows them to effectively and fast response local needs and demands (Le and Liao, 2017). In the market in which competitors have strong competitive advantage and cultural impacts on demand is relevant, MNCs tend to adopt adaptation strategy (Haron, 2016).

To solve conflicts between local responsiveness and cost pressure, integration-responsiveness framework is developed. According Devinney et al. (2000), the framework has two important strategic needs: 1) integrating local presence into global value chain activities and 2) developing products and services to response local needs. This framework has the purpose to balance the needs of globalisation and localisation (Le and Liao, 2017). By business network, international companies absorb market knowledge and customer insights of a host country from strategic alliances and integrate those strategic alliances into its global integration of value chain activities (Meyer and Su, 2015). MNCs adopt transactional strategy to balance the conflicts between global integration and local responsiveness (Haron, 2016). Transactional strategy focuses on both cost effectiveness and local responsiveness through though using flexible approach (Meyer and Su, 2015) The flexible approach means to use standardisation if it is feasible and adopt adaptation strategy if local responsiveness is appreciated (Vrontis, 2003).

2.7 Market Mix

Market mix is an essential framework for a company, covering product, price, place and promotion. It refers to a group of marketing techniques which are designed for companies to achieve its marketing objectives in target market (Kotler, 2000). A MNC’s adaptation or standardisation directly affect its marketing mix in international market.

2.8 Consumer Buying Decision Process

Consumer buying decision process consists of five major stages as figure 3 shows, including problem recognition, information search, evaluation of alternatives, buying decision and post-purchase behaviour.

In the stage of problem recognition, consumers realise a need or problem that can be met or solved by consumption (Qazzafi, 2019). Both internal and external stimuli can make consumers recognise the problem. Internal stimuli can be hungry, whereas external stimuli may be an advertising or a friend’s purchase.

In the stage of information search, consumers tend to search information from those who they trusted such as friends and family members (Kotler, 2017). At present, they tend to seek purchase information from social media and trust in online word of mouth.

The stage of alterative evaluation means that consumers assess alternatives and then generate their purchase intention or directly make a purchase (Kotler and Keller, 2016).

Purchase decision stage means that a consumer finally makes decision. However, before the decision, consumers also can be affected by unexpected factors such as economic crisis and other’s suggestions (Kotler and Keller, 2016). Those people who consumers trust can strongly affect their purchase decisions, such as Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs), spouses and so on.

Eventually, consumers have post-purchase behaviour which is complicated psychological process. In general, they evaluate the gap between expected quality and perceived quality (Qazzafi, 2017). If perceived quality exceeds expected quality, they tend to be satisfied. Otherwise, they are unsatisfied. Then, they share their opinions, experiences, and attitude toward their purchase with others perhaps by social media. They generate word of mouth thus affecting others.

Figure 5: Consumer buying decision process

2.9 Research Hypothesis

Based on market mix and above theories, this research devises the following research hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1

H0: there is no relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation in products and consumer buying decisions.

H1: there is a relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation

in products and consumer buying decisions.

Hypothesis 2

H0: there is no relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation in promotion and consumer buying decisions.

H1: there is a relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation

in promotion and consumer buying decisions.

Hypothesis 3

H0: there is no relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation in price and consumer buying decisions.

H1: there is a relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation

in price and consumer buying decisions.

Hypothesis 4

H0: there is no relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation in place and consumer buying decisions.

H1: there is a relationship between the integration of standardisation and adaptation

in place and consumer buying decisions.

3.0 Research Methodology

In accordance with Saunders and Thornhill (2012)’s research onion (Figure 5), this research adopts the following research methodologies: realism, case study, mixed methods, cross-sectional time horizon, interviews and questionnaires as data collection methods. It collects both primary and secondary data to analyse the Chinese wine market and expansion of Penfolds. Also, it uses both interviews to collect qualitative data and questionnaires to gather quantitative data. Therefore, it adopts case study to generate in-depth findings.

Figure 6: Research Onion

(Source from: Saunders and Thornhill, 2012)

3.1 Realism

This dissertation adopts a realism philosophy depending on the standpoint that independent reality exists in the human mind. Realism is built on the assumption that a scientific approach generates and develops knowledge. Realism focuses on both scientific approach and subjectivities, which is suitable for social studies (Kervin, 1999). By realism philosophy, this research can conduct both quantitative and qualitative analysis for the case study of ‘Penfolds’ expansion in China’.

Positivism and interpretivism philosophy are not suitable for this dissertation. Positivism generates law-like findings by scientific approach, which is more suitable for experiments in laboratory, but it is not appreciated for human and social studies, as its strict research framework can hinder researchers to discover potential variables (Kervin, 1999). Interpretivists criticise that positivism is not appreciated for social study and to investigate human behaviour as its structure is more suitable for experiments in laboratory. Meanwhile, interpretivism is criticised for its overmuch dependence on subjectivities. Interpretivism relies on researchers’ feelings and experience to perceive research phenomenon, so the results of interpretivism-based studies are arguable and unreliable (Kervin, 1999). Realism can be viewed as the integration of positivism and interpretivism philosophy. It does not adopt the rigorous framework of positivism which could hinder researchers to explore variables. Also, realism is much more objective than interpretivism because it relies on a scientific approach.

3.2 Deductive Approach

Deductive approach is applied into this dissertation. Deductive approach is workable under realism philosophy, which explains a research phenomenon based on the existing theories and knowledge (Bernard, 2011). Deductive approach uses reliable theories to explain a research phenomenon. It sticks to the path of logic in a most closely way. This research approach is effective and timesaving because it directly targets at research questions and phenomenon. The approach makes reasoning from the general to the particular. It means that this dissertation adopts general theories and knowledge to explain the Chinese wine markets. It relies on a large collection of literature to collect and analyse a wide scope of knowledge and it allows researchers to complete study tasks within short time. Deductive approach has the advantages to make explanations of causal relationships, measure concepts in quantitative way, and make generalisation of research findings.

Based on deductive approach, this dissertation has the following stages: 1) collecting and analysing existing theories and knowledge; 2) designing and developing research questions; 3) collecting data from the research phenomenon; 4) discussing the results of primary data with the theories and knowledge; and 5) generating conclusions and recommendations for the Chinese red wine markets.

Inductive approach is not applicable for this dissertation because it targets to generate new theories. It emphasises on understanding dynamics, robustness, emergence, and resilience. In social studies, the approach is normally used to explore research questions and generate insights (Goddard and Melville, 2004). However, this dissertation already has specific research questions and has no plan to prove any new theory. Thus, inductive approach is not suitable for this research.

Inductive approach adopts bottom-up way studying a certain phenomenon to generalise universals. By contrast, deductive approach follows top-down starting with general knowledge to apply knowledge into a phenomenon. Deductive approach is suitable for the dissertation to use general knowledge to apply into the Chinese wine markets. Furthermore, deductive approach emphasises on prediction of transformations, ‘mean’ behaviour, examining assumptions and building most likely future (Bernard, 2011).

Nevertheless, it is important to understand the limitations of deductive approach. The results of deductive approach-based research rely on the validity of the existing theories and knowledge. If the theories and theories are not true, the result is not reliable. Thus, this dissertation ensures the reliability of theories and knowledge which are used in the research. It only analyses and implements the theories and knowledge from reliable sources such as journals.

3.3 Research Strategy: Case Study and Survey

This research adopts case study as research strategy. Case study allows this research to collect deep data and generate insights. It is suitable for those research phenomena which strongly incorporate into its context (Kervin, 1999). This research study on Penfolds’ expansion strategy in China, and this phenomenon is strongly related with Chinese context. Therefore, case study is a proper research strategy for this dissertation. More importantly, case study supports a variety of sources of data including newspaper, documents, reports etc. With the help of case study, this research adopts both secondary and primary data to analyse Penfolds’ strategy in China and then identify whether or not the strategy is applicable for other wine brands. On the other hand, experiment and focus group are not applicable in this research because they do not support both second and primary data. They are unable to help the inquirers to accomplish the research aim. Therefore, case study is an appreciated research method. By using case study, this dissertation can have a mixed research covering both quantitative and qualitative approach.

This research uses secondary data to analyse the case of Penfolds’ expansion in China. The secondary data comes from Penfolds’ official website, TWE’s annual report and other reliable sources. The result of the analysis of secondary data is used to develop questionnaires and interviews.

Also, survey is used in this research to generalise the findings of the case study. The purpose of the survey is to make recommendations for all luxury wine brands’ expansion based on Penfolds’ success. The usage of survey can cover the limitation of case study that cannot generate universals. Survey is consistent with positivism philosophy and can effectively collect quantitative data (Bernard, 2011). Within short-term, researchers can gather a large sample size.

3.4 Mixed Research

As a mixed research, this dissertation adopts both quantitative and qualitative analysis, which aligns with realism and case study. Qualitative analysis enables the research gains insights by allowing inquirers to directly perceive the research phenomenon. Secondly, by using quantitative analysis, this research can generate reliable and convincing findings. The qualitative analysis is used to explore variables and study the expansion strategy of Penfolds. Then, the quantitative analysis is used to test the research hypotheses based on Chapter two – Literature Review and findings from the qualitative analysis. The aim of the quantitative analysis is to identify whether or not the strategy of Penfolds can be applied to other wine brands from Australia and other countries.

3.5 Time Horizonal

This research adopts a cross sectional rather than longitudinal time horizon. In this sense, it only gathers primary and secondary data for once. The research does not aim to make any historical comparison, so cross-sectional time horizonal is proper. Moreover, longitudinal time horizon requires the research to collect time for several times, but the research must be completed within 6 months (Wilson, 2010). Therefore, it is not applicable for the research.

3.6 Data Collection

3.6.1 Interviews

This research adopts interview to collect primary data. Interviews allow the researcher to gain insights and collect qualitative data, which aligns with realism and case study. More importantly, interviews enable the researcher to observe the responses of respondents including their answers, body languages and facial expression, so the researcher can ask further questions and personalised questions to gain insights. This, this research adopts semi-structure interviews.

The interview question is designed based on the analysis of the secondary data. The specific interview question is showed at Annex III – Interviews.

This research plans to interview 8 wine purchasers who used Penfolds’ products and have a wine consumption habit in China. The research pays attention to the selection of the respondents and select the respondents in accordance with demographic and behavioural segmentations (Table 1).

|

Respondent number |

Demographic segmentation |

Behavioural segmentation |

|

1 |

24 years old Male Self-employed Single Middle class |

Having habit of drinking wine Drinking 10 to 12 bottle of wine per month Drinking Penfolds on special occasion |

|

2 |

30 years old Female Professional Having a romantical relationship but unmarried Upper middle class |

Strong preference to red wine Drinking 5 to 10 bottles per month Drinking Penfolds is a habit

|

|

|

35 years old Male Entrepreneur Upper class Divorced Living alone |

Drinking alcohol basically everyday Having red wine collection Drinking 10 to 20 bottle red wines per month |

|

4 |

40 years old Female Household Married Living with a husband and a child Married |

Drinking red wine as the way of self-releasing Drinking Penfolds for special occasions such as holiday, anniversary, birthday, etc.

|

|

5 |

45 years old Male Manager Married Upper middle class |

Drinking alcohol in social events such as dinner Preferring red wine Drinking Penfolds regularly |

|

6 |

48 years old Female Household Married Upper class |

Preferring to red wine Drinking wine in social events But drinking temperately Drinking 1 to 3 bottles of red wine per month |

|

7 |

50 years old Male Professional Married Upper class |

Alcohol consumption habit Drinking wine everyday Consuming 20 – 25 bottles of wine per month Loyal to Penfolds |

|

8 |

55 years old Male High-level manager Upper class |

Drinking alcohol once a week, averagely Drinking about 4 bottles of Penfolds per month and loyal to the brand |

Table 1

3.6.2 Questionnaires

Questionnaire is applied in this research to collect quantitative data used to test research hypotheses. It is effective in gathering quantitative data because it can gather a mass of numerical data from a large research population (Kervin, 1999). The numerical data from questionnaires can be analysed by statistical package in an effective way. Online questionnaires can be widely and rapidly spread via the Internet. Inquirers can share the link of online questionnaires by e-mail and in social medias to reach research populations. Although the design process of questionnaires can be complicated, the data analysis of questionnaires can be effective and efficient by using statistical software package such as SPSS. More importantly, online questionnaires are more affordable to student researches than other data collection measures such as experiments.

This research adopts online questionnaires and devises the website for the questionnaires on www.wjx.cn. The questionnaires have three sections.

To be noticed, the questionnaire is designed based on the data analysis of the secondary data and the interview. The first section is used to measure the drinking and consumption habits of wine. It asks how many bottles of wine does a participant purchase and drink per month? What occasion does a participant drink? When does a participant drink high-end wine? Have they ever drunk Penfolds?

The second section is designed to test research hypotheses. Questions in this section provides Likert-scale options ranging from strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree and strongly agree.

The third section collects demographics information of participants, including their gender, disposable income, age, and education background.

To test the research hypotheses, the questionnaires target at those participants who habit of consuming middle and high-end wine and strong consumption capabilities. The purpose of the questionnaires is to identify whether or not the strategy of Penfolds can be applied to other wine brands from Australia and other countries.

Additionally, this research collects 160 questionnaires to generate a greater representation of research population and contribute to reliability and validity of the results.

3.7 Sampling Technique

Self-selection is applied to access participants of the online questionnaire. By this sample technique, they involve in this research based on their own willingness rather than their financial rewards. By this way, the research can prevent those participants who do not have wine consumption habit but fulfil the questionnaires for financial rewards. Self-selection enables the researcher to build a big sample size within short-term (Saunders et al., 2012). More importantly, this sample technique enables the researchers to collect data from those participants which are easy to access.

Although self-selection has a low representation of research population, probability sampling techniques are not applicable in this research. They require researchers to build a mechanism ensuring that each individual of their research population has the equal opportunity to be selected to provide data. This means that these researchers have to build research database covering all research population. Nevertheless, it is impossible for this dissertation to develop a database covering all high-end wine consumption population. Thus, non-probability sampling technique is appreciated.

This research spreads the link of the online questionnaires in Chinese social medias including WeChat, Weibo, Zhihu, and Douban to directly access research population. Also, it directly sends the link to potential participants by e-mail or WeChat.

3.8 Research Ethics

The research attaches importance to ethical conducts. Firstly, it involves no deception and is fully honest to research participants and respondents. It illustrates its purposes, aims and objectives to potential respondents and participants by a consent letter. Secondly, this is an innominate research that does not collect name, contract and identity information of participants and respondents. Thirdly, all data is reserved in the researcher’s work laptop and only the University and the researcher can access the data. This research does not debrief its results in order to avoid disputes. More importantly, it involves no commercial secretes.

4. Data Analysis

4.1 Qualitative Analysis

4.1.1 Secondary Data Analysis of Expansion Strategy of Penfolds

Chinese Culture

Given that culture has strong impacts on expansion strategy and performance of an international brand, it is prominent to understand Chinese culture to study Penfolds’ expansion. Chinese people have preference to imported products from Western countries and they consider Penfolds as a premium brand (Shaw, 2012). According to China Wine Competition (2020), the most important task to establish a wine brand is to understand Chinese consumer behaviour, preferences, and habits. Chinese consumers use their high-end wine consumption to demonstrate their social status and level of their success. Also, they exchange high-end wine as gifts or given on special occasions, so they are highly concerned about brand image (China Wine Competition, 2020).

Motives of Internalisation

Penfolds’s expansion was motivated by the rising Chinese wine market. Moreover, it was confident that had competitive advantages and leverage them to gain economic returns in China. Penfolds invested in China to explore the increasing demands. According to Aurthur(2019), Chinese wine market increased by 26% between 2014 and 2016 and grew by 7% between 2016 and 2010; and 40% of wine sold in China is imported wine. Penfolds realised that Chinese people have been more willing to spend more for high-end wine. Growing Chinese market motivated Penfolds to launch its expansion and continuously increase its commitment.

Another motive is competitors’ expansion in China. French wine brands accounted for 12% of market share in China in 2019 while their market share has been declining, whereas Australian brands have been increasing their market share (Aurthur, 2019). More importantly, the Australian wine brand, Yellow Tail has expanded into China, and Rawson’s Retreat as the subsidiary of TWE also penetrated into China. The expansion of competitors and industry players motived Penfolds’ expansion.

Moreover, the traditional wine markets have been declining and becoming more saturated and competitive. The revenue of Australian wine production industry decreased 2.9% in FY 2017 (Statista, 2020). Wine consumption in developed countries has been showing a declining trend (Ritchie and Roser, 2018). Thus, wine manufacturers have been increasing their involvement and commitment to emerging markets.

Uppsala Model

Penfolds adopts a gradual step to expand into China. According to Liang (2020), Penfolds expanded into mainland China in 1995. The brand had been collecting experience of international expansion in other markets before its expansion to China. It has been active in developing countries including New Zealand, European countries, the US, Singapore, Hong Kong, and then mainland China. In accordance with Uppsala model, the brand started to expand to New Zealand which is geographically and cultural close to Australia and to European countries and the US in the latest century. The brand has been using its international experience to increase the presence and involvement of Penfolds in Asia. TWE has been active in over 100 countries (Jenkins, 2016). This means that the company has sufficient experience of internationalisation. TWE had achieved success in expanding in South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan before it expanded into mainland China (Jenkins, 2016). It has been effectively collecting marketing knowledge and customer insights in Hong Kong which has the culture similar with mainland China. More importantly, before the expansion of Penfolds, TWE had used some brands to expand into China to gain market knowledge and customer insights as well as develop business network. After Penfolds expanded into China, it gradually increased its commitment and involvement in the market. It started with exporting via agent in 1995. After years’ operation TWE built regional head office as a subsidiary in Shanghai, China to further explore the market (TWE Global, 2020).

OLI Model

Ownership advantage

Under the management of TWE, Penfolds has enterprising advantages in Chinese market, including trademark, brand image and international experience.

Location advantage

However, Penfolds does not have location advantages in China where has no natural and created resources for wine manufacturing.

Internalisation advantage

Penfolds does not have internalisation strategy in China. It has speciality and expertise in grape planting and wine manufacturing, whereas it does not have sufficient business networks for distribution in China. Meanwhile, the high cultural barriers in China hinder Penfolds to develop distribution networks by itself.

Given that the brand has no location and internalisation advantage, export is the most suitable entry mode for it.

Entry strategy and Entry Mode

Entry mode

Penfolds adopt direct exporting to access to Chinese market. According to TWE Global (2020), TWE leverages the business model emphasising on distribution by its own local team which directly own and administrate relationships with its wholesale and retail partners. The company aggressively invested in its business model to push direct engagement. It expects to the business model to achieve success in China in long-term. With the help of the business model, the brand has been strongly controlling its export and brand image in China. Also, the company has been increasing availability of luxury wine throughout China by improving its distribution and introducing new products (TWE Global, 2020).

An Integration of Standardisation and Adaptation

Penfolds adopts the strategy of integrating standardisation and adaptation. It focuses on standardisation in term of product and brand to ensure the consistence of its global brand by selling the exact same products in China. However, the brand also adopts adaptation in term of marketing strategy. The specific standardisation and adaptation practices of Penfolds can be analysed by market mix.

Market Mix

Place

Penfolds takes advantage of localisation/adaptation strategy in term of place. It participated into localised e-commerce platforms and address the major local issue – counterfeit. TWE Group built direct relationships with Chinese e-commerce retailers including Alibaba and JD Mall. Since 2015, TWE has been using Alibaba’s e-commerce platform (TMall) to sell Penfolds (Brennan, 2019). In 2017, it developed a partnership with Alibaba focusing on brand-protection (Brennan, 2019). TWE is in Alibaba’s Good Faith takedown program and a member of the Alibaba Anti-Counterfeiting Alliance Also, the company has been developing its relationship with Alibaba’s Brand Cooperation Team (ABCT). Thus, the partnership can strongly strike counterfeits in Alibaba’s platform (Brennan, 2019). According to TWE’s director of Intellectual Property (IP), by the partnership, the company can collaborate with both Alibaba and local law enforcement to conduct both offline and online enforcement against counterfeits. Striking counterfeits is the major task of the partnership. It can address the issue in local market to protect the interests of the local customers. Furthermore, the brand participated Alibaba’s 9.9 Wine Festival to have direct conversation with customers to discuss about counterfeits issues, quality issues and their demands (Brennan, 2019). Thus, with the help of Alibaba, the brand can acquire market knowledge and customer insights.

Meanwhile, as the second largest online shopping mall after Alibaba’s Taobao, JD Mall has been expanding its partnership with Penfolds. In 2016, the online retailer reinforced its partnership with Penfolds to be the first to sell the new Penfolds Max’s wine (JD. Com, 2016). Then, JD Mall has been increasing the product types of Penfolds to satisfy the rising demands in China.

Price

Penfolds adopt standardised pricing strategy in China, which can be viewed as a pricing standardisation practice. The brand uses international pricing standardisation to reserve its brand image in China. According to Annex II, the Penfolds BIN 2 is sold at CN 938 Yuan (AU$ 192.64) for 6 bottles, whereas its price is AU$ 28.99 per bottle in China (AU$173.94 for 6 bottle). More importantly, Penfolds pays higher tax in China than Australia. To be specific, it needs to pay 14% imported tax, 16% VAT and 10% excise tax (Wang, 2018). However, the wholesale tax of wine in Australia is 29% (Australian Government, 2020). Besides the higher tax and transportation costs, the prices in China is basically equal to those in Australia.

Promotion

Penfolds uses adaptation/localisation strategy to develop promotion activities in China. As Annex I shows, the official website of the brand for mainland China is slightly different with that for Australia. For Chinese market, the official website focuses on products at front page by showing Penfolds Collection series on the top. Also, it does not show the special dessert. Instead, it focuses on the introduction of Penfold Magill Estate and its restaurant, even though the two places are in Australia.

Penfolds attaches importance to localisation in communication. It does not simply translate its marketing message from English to Chinese. Instead, it develops localised marketing messages in alignment with the uniqueness of Mandarin. For example, Penfolds 111 A is described as ‘a very rare release’ in English message, whereas the Chinese marketing message uses the word ‘excellence’, ‘extraordinary’, and ‘exclusive’ in Mandarin to describe this product (Annex I). This focuses on the high quality, performance, and exclusivity of the product in China.

More importantly, Penfolds allows its licensed distributers to conduct price discount and other promotional activities such as gift, bundling, and gift set. These are important localised practices that aligns with Chinese people’s consumption habits and demands. Given that Chinese people are concerned about prices when they are making purchase decisions, Penfolds offer 2 to 3 free bottles of wine when consumer purchase a 6-bottle-box of wine. These free bottles are less-known brands and cheaper, whereas they can increase Chinese customers’ perceived value and counteract the high prices of Penfolds. This is consistent with Chinese value of thriftiness. Also, to adapt to Chinese people’s purchase habit of gift giving, the brand offers gift package and gift set. The product packages designed on the basis of Chinese people’s preference and aesthetics.

Product

Penfolds balances standardisation and adaptation strategy in term of product. It does not develop products especially for Chinese market, currently, whereas it focuses on those products which align with Chinese people’s preference and tasty.

4.1.2 Results of Interviews

The primary data collected from the 8 respondents is analysed in this section.

1) How often do you high-end red wine?

‘…basic everyday…’, ‘…5 days in a week…’, ‘…once a week…’, ‘…twice a week…’ according to the respondents

All respondents have a habit of drinking high-end red wine from heavy users, moderate users, and light users. This means that they have sufficient experience and relatively more knowledge about high-end red wine. Thus, studying these respondents can gain insights of Chinese high-end wine consumers.

2) What kind of occasions do you drink? Social events (dinner), drinking with friends, and/or drinking on festivals

‘Dinner’, ‘Socialising’, ‘Drinking with business partners’, ‘before sleeping… good for health…’, ‘Making friends’, ‘for leisure time’, ‘for relaxing and self-releasing’, ‘for sleeping’, according to the respondents

This research finds that older respondents have the tendence of drinking for social occasions. They drink to develop business networks, socialise, social events especially for dinner. Also, some older respondents have the habits to drink before sleep. They believe that moderate or light drinking is good for sleep and health. However, younger respondents are more likely to drink during leisure time, release themselves, and drink with their close friends.

3) Why do you drink high-end wine?

‘…To accommodate friends…’, ‘…to have high quality life…’, ‘…most of my friends also drink…’, ‘…I love wine, so I want to drink some good wine…’, and ‘…this is my love…’, according to the respondents.

They use high-end red wine to accommodate their friends to expand and nurse social and business networks. There is a pattern that these respondents drink Penfolds because their friends also drink. Younger respondents drink high-end wine because they have desire to enjoy life and pursue high-end life. They have a luxury lifestyle who can afford it.

4) How do you get wine such as Penfolds? Did you buy for yourself, or others give wine as a gift?

‘…gift…’, ‘…a present on festival…’, ‘…other gave it to me…’, and ‘…purchasing by myself…’, according to the respondents.

Young respondents purchase Penfolds’ wine by themselves. However, some older respondents receive Penfolds’s products as gifts. They are likely to receive such gifts on Chinese traditional holidays. Meanwhile, it is normal for them to receive such gifts when others ask them help or a favour. Penfolds’ products are giving away as a gift to nurse a relationship.

5) Why do you regard Penfolds as a luxury brand?

‘… Price…’, ‘…expensive…’, ‘…all people I know consider it as luxury…’, and ‘taste’, according to the respondents

Many respondents use price to judge the luxury of Penfolds. A respondent reveals that some Penfolds’ products are sold at over 30,000 CNY making him believe it is a luxury brand. Price is an important factor of the sense of luxury. Other consider word of mouth of those people they know including family, friends, co-workers, etc. Only two respondents perceive this brand as luxury because its taste and product quality.

6) How do you know the reputation of Penfolds?

‘…Friend recommendation from social media…’, ‘…acquaintance’s recommendations from dinners…’, ‘…content from social media…’, and ‘…magazine…’, according to these respondents.

Word of mouth from friends and social media is the major way that these respondents know Penfolds. Some respondents experience Penfolds’ wine in social occasion especially dinner and they received the brand knowledge from their friends. Some young respondents saw that their friends shared the picture of Penfolds in social media. Some respondents read articles about Penfolds from magazines.

7) What make you prefer to Penfolds?

‘…its name is lucky…’, ‘…the name means reaching to treasure…’, ‘…a good name for socialising event, for celebration, and for festival…’, ‘…good taste…’, ‘…good quality…’, and ‘…it becomes a habit…’, according to these respondents.

Many respondents indicate that they prefer to Penfolds because of the brand name. Penfolds in Mandarin means ‘road to fortune’ and ‘fitting to fortune’. Both younger and older respondents show that they love the brand name which is especially appreciated for gift-giving, festival, social events, and celebration because it is auspicious meaning. Fewer respondents indicate that they prefer Penfolds because of its product quality such as taste. A respondent has a habit of drinking Penfolds.

4.2 Quantitative Analysis

4.2.1 Frequency Analysis

Gender distribution

This research totally has 160 participants including 83 males (51.9%) and 77 females (48.1%).

|

|

Male |

Female |

|

Number |

83 |

77 |

|

Percentage |

51.9% |

48.1% |

Table 2: Gender Distribution

Figure 7: Gender Distribution

The age distribution is showed in Table 3. The large

|

|

Number |

Percentage |

|

Below 25 |

13 |

8.1% |

|

26 – 30 |

37 |

23.1% |

|

31 – 35 |

24 |

15.0% |

|

36 – 40 |

20 |

12.5% |

|

41 – 45 |

21 |

13.1% |

|

45 – 50 |

11 |

6.9% |

|

51 – 55 |

17 |

10.6% |

|

Above 55 |

17 |

10.6% |

Table 3: Age Distribution

As figure 8 shows, the age group of 26 – 30 is the largest group accounting for 23.13%, followed by 31-35-years-olds (15.00%), 41-45-years-olds (13.13%), etc. The smallest age group is 6.88%.

Figure 8: Age Distribution

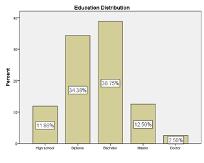

38.75% of participants have a bachelor degree, followed by 34.38% diploma, 12.50% master, 11.88% high school and 2.5% doctor.

Figure 9: Education distribution

43.75% of participants have 20,001 to 30,000 disposable income, followed 35.00% of participants with above 30,000 disposable income. 17.50% of participants have 10,001 to 20,000 disposable income. Only 3.75% of participants have below 10,000 disposable income. This means that most of participants has sufficient monthly disposable income to support them to purchase high-end red wine.

Figure 10: Disposable Income

As table 4 shows, 45.0% of participants basically drink every day, followed by 5 days per week (20.0%), once a week (14.4%), below 4 times a week (12.5%), and below twice a week (8.1%). This means that all participants have a habit of drinking high-end wine who therefore can offer meaningful data.

|

How often do you drink high-end wine (over CNY 180 per bottle)? |

||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Basically everyday |

72 |

45.0 |

|

5 days a week |

32 |

20.0 |

|

About once a week |

23 |

14.4 |

|

Below 4 times a week |

20 |

12.5 |

|

Below twice a week |

13 |

8.1 |

Table 4

As Table 5 shows, the reasons to drink include business networks (38.1%), socialising (27.5%), fan with close friends (26.9%), and for relaxing (7.5%). Most of participants have social purposes to drink.

|

Why do you drink? |

||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Socialising |

44 |

27.5 |

|

Developing and maintaining business networks |

61 |

38.1 |

|

Having fan with close friends |

43 |

26.9 |

|

For relaxing |

12 |

7.5 |

Table 5

A large number of participants receive high-end wine as gift from others (46.9%) and 53.1% of participant purchase it by themselves.

|

How do you get high-end wine? |

||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Receiving such wine from others |

75 |

46.9 |

|

Purchasing it by myself |

85 |

53.1 |

Table 6

43.1% of participants spend 0 – 2,000 CNY in wine consumption, followed by 2,001-6,000 (22.5%), above 6,000 (16.3%), and hard to say (18.1%).

|

How much do you spend on wine monthly? |

||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Hard to say |

29 |

18.1 |

|

0 – 2,000 |

69 |

43.1 |

|

2,001 – 6,000 |

36 |

22.5 |

|

Above 6,000 |

26 |

16.3 |

Table 7

Product

A luxury or auspicious brand name in Mandarin is important, given that large proportions of participants agree and strongly agree that they will purchase a brand with such name. However, the fitness to Chinese people’s taste is not very important to them but it is a relevant factor. Only 15.0% of participants agree and 12.5% of participants strongly agree that they will purchase a product that fits Chinese people’s taste. Direct export is not very important, but it is a relevant factor affecting Chinese consumer buying decisions.

|

Strongly disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|

|

A brand / product name has a lucky or auspicious meaning |

12.5

|

5.6

|

23.8

|

35.6

|

22.5 |

|

A product fits Chinese people’s taste. |

28.7

|

30.0

|

13.8

|

15.0

|

12.5 |

|

An international famous brand directly exports its product to China |

26.9

|

30.6

|

16.9

|

13.1

|

12.5 |

Table 8

Promotion

A large proportion of participants agree (33.8%) and strongly agree (36.3%) that they will purchase a beautiful and luxury gift set. Thus, beautiful and luxury gift set is a strong factor affecting customers to make purchase decision. Also, many participants strongly agree or agree that they will purchase a brand that offers gift. This means that gifting is an important promotion strategy affecting Chinese consumer purchasing decisions. Additionally, 26.9% of participants agree and 31.3% of participants strongly agree that sales promotion making perceive benefits motives them to purchase. Thus, sales promotion is an important promotion strategy.

|

Percent % |

Strongly disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|

A brand sells beautiful and luxury gift set. |

9.4

|

4.4

|

16.3

|

33.8

|

36.3

|

|

A brand provides gift when consumer purchases wine. |

12.5

|

12.5

|

28.1

|

26.9

|

20.0

|

|

A brand has sales promotion making me perceive benefits |

6.3

|

13.8

|

21.9

|

26.9 |

31.3

|

Table 9

Price

Many participants agree (20.0%) and strongly agree (13.8%) that they will purchase a brand whose prices in China are same in oversea. However, some participants strongly disagree (19.4%) or disagree (18.1%), This suggest that standardising price is not a very important factor but relevant factor affecting Chinese consumer buying decisions. A higher price than Chinese wine is a strong factor affecting the decisions, as 35.0% of participants agree and 29.4% of participants strongly agree that they will purchase a brand which is more expensive than Chinese wine. This implies that they use price to perceive quality, who assume that higher price brings higher quality and the sense of luxury.

|

Percent % |

Strongly disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|

The price of the brand in China is in the same level of that in oversea. |

19.4

|

18.1

|

28.7

|

20.0

|

13.8

|

|

The price of the brand is higher than that of Chinese wine. |

12.5

|

5.0

|

18.1

|

35.0

|

29.4

|

|

The price of the brand has a wide range from relatively low level to very high level. |

10.6

|

16.3

|

10.6

|

26.3

|

36.3

|

Table 10

Place

The easiness to purchase is very important, because 26.9% of participants agree and 34.4% of participants strongly agree that they will purchase a brand if it is easy to purchase. Easiness to purchase online also is an important factor. More importantly, counterfeit is very important that strongly affect consumer buying decision.

|

Percent % |

Strongly disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|

It is very easy to purchase the product. |

16.9

|

5.0 |

16.9 |

26.9

|

34.4

|

|

I can easily buy the product from large online shopping malls such as Taobao |

16.3

|

16.3

|

27.5

|

17.5

|

22.5

|

|

I do not need to worry about counterfeits when I purchase its products |

16.9

|

10.6

|

18.8

|

26.9

|

26.9

|

Table 11

4.2.2 Correlation Analysis