Analysis of the Development Prospects of Musicals in China, Case Study of the Drama, ‘On Leaving Cambridge’

Acknowledgement

I really appreciate Mark Dorfman who has spent his valuable time in reviewing my dissertation and offering suggestions. Moreover, I would like to thank all respondents of this research.

Abstract

This dissertation aims to look at the development prospects of musicals in China by focusing on the case study of the drama, ‘On Leaving Cambridge Again’. The purpose of this dissertation is to identify the development prospects of the Chinese musical market through this case study and provides suggestions for increasing viewers’ interest in musicals.

The dissertation used both quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative data was collected by questionnaires, while interviews were used to collect qualitative data. As a descriptive research, it adopted case study to explore out insights and self-selection sampling technique.

The major issue of Chinese musical is the lack of demands. Younger generations are less interested in musicals with the rise of digitalisation and older generations prefer traditional opera. Chinese musical industry lacks government support because the government is committed to supporting traditional opera. In the context of globalisation, foreign musicals face three challenges to expand into China. Moreover, Chinese musical industry has many internal problems. The industry lacks a professional stage and management team. It lacks an effective business model and has not fully achieved industrialisation yet. It has no professional theatres, management and is short of investment, professional actors, and good stories.

Chinese audiences of musicals demand better actors and actresses, more professional stage, live bands, better sound effect, and novel story. The improvements in these factors can increase demands. Chinese audiences expect creative and novel stories and scripts in musicals. Chinese audiences demand better musical infrastructures including sound and stage effects. They desire a live band that can offer great watching experience.

Further research should increase its sample size to increase representativeness of research population and improve generalisation of its findings. Further research can explore an effective business model and focus on management. They can identify the business model and management of foreign musical businesses and identify whether or not these can be applied in China. Further research can explore how foreign musicals can achieve effective localisation.

1.1.1 Shanghai, The Centre of Theatres

Chapter 2 – Literature Review – Theatre and its Marketing

2.1 The Development of Western musical theatre

2.2 The Development of Musical Theatre in China

2.3 The Challenges for Musical Theatre in a Global Environment

2.4 The Challenges for Musical Theatre in a Digital Environment

2.4.2 Digitalisation in Musical Theatre

2.5 The Audiences for Musical Theatre

2.5.1 Marketing Musical Theatre

2.5.2 The Chinese Market for Musical Theatre

2.5.3 Financial Aspects of Musical Theatre

2.5.4 Developing New Audiences for Musical Theatre

2.6 Development Prospects of Musicals in China

2.6.3 Obstacles to the Development of Chinese Musical Theatre

3.6 Cross-sectional Time Horizon

3.9 Research Population and Sample Size

4.1 Introduction and background to the case study

4.2 Data Analysis of Questionnaires

4.3 Data Analysis of Interviews

5.2 Limitations and Further Research

Appendix I – Questionnaires and Interviews

Appendix II – Statistical Results

Chapter 1 - Introduction

1.1 Background Information

With the rise of the Chinese economy, the demand for musicals has been increasing in the country, and at the same time the widespread and immense popularity of digital technologies has been diversifying entertainment methods. People have a variety of choices for their leisure time, such as movies, online video games, social media, and so on (Kooh, 2020). Although it is clear that globalisation also has been enriching people’s entertainment, facilitating cross-border cultural exchange, and expanding people’s horizon, the demands and desires of musicals’ audiences have been becoming increasingly more dynamic and flexible due to globalisation, and it has been becoming increasingly more difficult to satisfy the needs and wants of audiences (Stokes, 2014). In an era of digitalisation and globalisation, the prospect of musicals is challenging and questionable.

In Western countries, musicals have consolidated their audience base and are viewed as culturally important. However, the audience base of musicals is much weaker in China, which brings more challenges to the development prospects of the Chinese musicals.

The history of the Chinese musicals can be categorised into four phases. Between 1919 and 1944, Phase I emerged and was inspired by the May 4th movement, a group of Chinese youth revolting imperialism, and musicals were created and performed with the purpose of confronting with and criticising imperialism and appealing patriotism. During Phase 1, many classic musicals rose, including ‘Yangzi River’s Rainstorm’, ‘Countryside Song’, ‘Great Production of Military and People’, and so on, reflecting and describing the revolutions against imperialism and colonialism from Western countries (Kooh, 2020). These musicals made great contributions to the localisation and nationalisation of musicals, by capitalising the experiences of Western musicals. Phase II (1944 - 1955), the Phrase of foundation, started at the Yenan forum on literature and art, led by the Chinese communists. Thus, this Phase was oriented by the Chinese communists, with great and deep political influence (Kooh, 2020). During the phase, musicals were created and performed to describe and reflect farmers’ life, the contribution of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to farmers, and the appreciated relationship between CCP’s military and farmers. Since the foundation of Chinese People’s Republic country in 1949, CCP sought out a new path for the Chinese musicals focusing on portrayals of CCP, military and proletarians (Toby Simkin, 2020). The Centre Experient Opera was created and conducted cross-cultural communications with the Soviet Union. In 1964, the Chinese Cultural Ministry realised that Chinese opera needed a more open path and thus divided the Centre Experient Opera into two theatres (Kooh, 2020). Due to the lack of entertainment, the audiences were enthusiastic for musicals. Under the high-power distance and planned economy, the creation and performance of musicals were directly controlled and oriented by CCP. Between 1949 and 1965, the Chinese musicals had unprecedented prosperity. Between 1966 and 1976, the Great Culture Revolution, led by CCP, completely ceased the growth of musicals, and even threatened the survival of musicals (Toby Simkin, 2020).

During the Revolution, innumerable artists, singers and dancers were assumed to be capitalists or the representatives of capitalism and were murdered or locked up. After the 1970s, the Revolution was completely ended, and human resources for musicals were lost or aged (Toby Simkin, 2020). In Phase III (1980 – now), the Chinese musicals earned the opportunity to be re-born. The Chinese musical started to gain experience from Hong Kong and Taiwan. The Reform and Opening-up policy, initiated by Deng Xiaoping, provided the channel for cross-cultural communication. Countless aspects of Western culture including musicals, music and songs entered into the country by legal and illegal approaches. Western culture and values have been stimulating the Chinese people’s eyes and values (Toby Simkin, 2020). Meanwhile, Chinese musical practitioners combined Western opera model, light opera model and national opera model and then created the concept of Chinese opera. Phrase II and Phrase III were completely controlled and oriented by CCP and strongly affected by political influences. However, since the 2010s, the Chinese economy model has transformed into the Coordinated Market Economy (CME) (Toby Simkin, 2020). Even though there are still strict censorship and constriction on cultural products, CCP was no longer playing a dominant role in the creation and performance of musicals.

Even though China has entered the free market for decades, Chinese culture sectors and musical industry are still under strong regulation of the Chinese government and the CCP (Toby Simkin, 2020). The major capital is heavily investing in the filming industry, online music, etc. rather than the musical industry. Most musical players in the industry are supported by the government. Most theatres are developed and operated by the state or the government-related organisations such as the Ministry of Culture, local government, and state-owned universities or institutions. Broadway and Disneyland are only the few private players in the Chinese musical industry.

1.1.1 Shanghai, The Centre of Theatres

There are 260 modernised theatres around the country, whereas only 30% of them can have about 50 shows annually (Xijia, 2018). To be noticed, the situation is much better in Shanghai where the frequency of shows can reach twice in three days. Half of the 260 theatres are in Shanghai. Most theatres around the country are used to advocate traditional operas including Peking opera, Yu opera, etc. They are unable to support modern musicals (Xijia, 2018). However, symphony theatres are unable to support professional opera because of their lack of infrastructure. Even though Shanghai already has 130 theatres, there still lacks professional theatre which can support world-class musical shows. Their infrastructures including sound, lighting, stage decoration and technologies, etc. are unable to meet the requirements of world-class musicals. Furthermore, theatres in Shanghai lack differentiations and are homogenous. Only three theatres are differentiated that include Shanghai Grand Theatre, Cultural Plaza and Shanghai Concert Hall. Shanghai grand theatre was founded in 1998 and re-opened in 2005 (Soupu, 2017). Since then, it started to fund itself and was independent from government subsidies. Until 2016, it had operated over 2,600 shows and served 2.7 million audiences. Cultural Plaza is developed for those musicals targeting young audiences. Within 4 years, it had 1000 shows and served 1.2 million audiences (Soupu, 2017).

There are four dimensions to evaluate an international culture metropolis, including cultural attractiveness, tolerance to culture, and creativity & appreciation capabilities (Xijia, 2018). Theatre industry currently has a shortage of Shanghai. Averagely, Shanghai residents visit theatres once in three years, whereas the figure of European residents is three-times in a year. Thus, the theatre consumption in Europe is three times as that in China.

Furthermore, the ticket prices are too high for Chinese people. The prices in Shanghai account for 7% - 8% of per capita income, whereas the figure in developed countries is only 1% - 2% (Soupu, 2017). According to a survey, for every 46 Yuan decrease in ticket price, theatres can sell 35,000 more tickets annually (Soupu, 2017).

1.2 Research Aims and Purpose

This dissertation aims to look at the development prospects of musicals in China by focusing on the case study of the drama, ‘On Leaving Cambridge Again’. The purpose of this dissertation is to identify the development prospects of the Chinese musical market through this case study and provides suggestions for increasing viewers’ interest in musicals. This dissertation intends to promote the development of musicals in China. It aims to critically review the development of Western musical theatre, the development of Chinese musical theatre, the challenges for musical theatre in a global environment, the challenges in the digital era, and the audiences for musical theatre. Furthermore, the dissertation focuses on marketing activities of musical theatre, the Chinese market for musical theatre, financial aspects of musical theatre, and development of new audiences for musical theatre.

As part of its overall aims, the dissertation has the following objectives:

1) To critically analyse the challenges of the Chinese music theatres in the era of globalisation and digitalisation on the basis of existing literature

2) To identify the demands and interests of musicals’ audiences in China by primary data from questionnaires and interviews

3) To make recommendations for the development prospects of musicals in China

1.3 Research Questions

1) What are the challenges and issues of Chinese musicals in the context of globalisation and digitalisation?

2) What are the demands and interests of the audience for musicals in China?

3) What are the recommendations for Chinese musicals?

1.4 Research Significance

This dissertation is significant in that it helps the development of the Chinese musical, which is especially important in the era of digitalisation and globalisation. Digitalisation and globalisation are threatening the growth of the Chinese musical and distract people from them. The audiences are becoming increasingly more difficult to satisfy. The expected results of the dissertation contribute to the development of the Chinese musical industry, which is managerially significant.

Furthermore, it is significant to cover a research gap. The study that investigates on Chinese musical industry is rare. Jianfei (2011) studies the barriers to the growth of the industry and Kim (2015) illustrates the difficulties of an international joint venture between a Korean musical company and a Chinese musical company. The dissertation can cover the gap of the study of the Chinese musicals and enrich the understanding of the Chinese musicals. Thus, it has academic contributions to the Chinese musical industry.

Chapter 2 – Literature Review – Theatre and its Marketing

2.0 Introduction

This chapter critically discusses theatre and its marketing particularly in the context of China. The chapter engages the following vital issues: challenges to musical development from globalisation and digitalisation; and the growth of western musicals in China and the growth of Chinese own musicals. It reviews the literature related with the development of western musical theatre, the development of musical theatre in China, western musicals in China, and the challenges for musical theatre in the global environment and in the digital age. The chapter focuses on Chinese audiences for musical theatre, involving marketing musical theatre, the Chinese market for musical theatre, financial aspects of musical theatre, and developing new audiences for musical theatre. More importantly, the chapter illustrates the development prospects of musicals in China.

2.1 The Development of Western musical theatre

To predict the development prospect of Chinese musical market, it is important to take a historical view of the development of Western musical theatre.

In Western theatre, the theatrical performance along with music in musical theatre which integrates songs, spoken conservation, acting and dance. Modern musical theatre originated from antecedents which developed in the 18th century when pera and pantomime arose in England (Block, 2019). Then, the tide of colonialism spread them and contributed to the development of musical theatre.

In the USA, between the very late 19 century and early 20th century, hundreds of musical comedies were shown on Broadway, with the help of composers (Black, 1993). At the same time, musicals also were widely performed in London. To be noticed, George Edwards made trials on modern-dress, family-friendly musical theatre style, featuring popular songs, romantic banter and stylish spectacle (Evan, 2000). In this period, many remarkable and revolutionary composers of musicals emerged including Ivan Caryll, Lionel Monckton, P.G. Wodehouse, Victor Herbert, Edward Solomon, and F. Osmond Car (Black, 1993). In the early stage of the 20th century, musicals directly competed with operettas. Across the English-speaking world, a group of European composers adapted English to operettas and in English-speaking countries, the popularity of German-language operetta which had been dominant showed a decline trend. More importantly, some British and American composers and librettists developed musicals toward the integration of light, popular entertainment with consistency between its story and songs (Kislan, 1995). Meanwhile, the history of musicals during War World One suggests that political context has a relationship with the development of musicals. During World War I, the public made a strong demand on entertainment to escape from the dark time created by the war, which facilitated the development of musicals. Many large musicals emerged, such as Maid of the Mountains performed by 1,352 performances and Chu Chin Chow needed 2,238 performances (Weiß et al., 2019). Furthermore, many composers started to introduce new musical styles such as ragtime and jazz to musicals (Norton, 2002). With the support of the public, musicals were developing toward diversification. The public environment and social context during World War I facilitated the demands for musicals, thus pushing its demands.

The following history of musicals shows that the development of musicals is strongly associated with economy and technologies. Between 1900 and 1950, musical theatre composers and lyricists created the majority of popular music. The Great Depression strongly hit the development of musicals. Musical theatres became unaffordable to many people (Norton, 2002). Meanwhile, the rise of motion pictures threatened the development of musicals (Hischak, 2008). Motion picture started with silence but soon it had synchronized sound. In the 1920s, most musicals focused on a happy song-and-dance style (Weiß et al., 2019). Then, the creative musical workers started to experiment musical satire, popular books, and operatic scope. Under the competition of motion pictures, the musical survived and developed toward political satire.

At present, musicals still are popular in the UK. In 2016, the total revenue of theatre tickets reached 19 million and there were 44,135 performances in 2018 (Luty, 2017).

2.2 The Development of Musical Theatre in China

Prior to the Revolution and Opening-Up policy in 1980, the development of musical theatre in China was significantly affected by political influence from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (Liu, 2012). As mentioned in Chapter I, the three phases of the Chinese musicals are strongly associated with politics. Phase I (1919 – 1944) was inspired by the youth revolution movement against imperialism and supporting patriotism. Phrase II (1944 – 1955) was led by the CCP with the purpose of gaining support for communists (Zheng, 1990). After the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, musicals focused on praising the CCP, farmers and militaries. However, the Great Culture Revolution ceased all cultural development including musicals (Horner, 1999). Most workers of musicals including performers, artists, composers and lyricists suffered political persecution (Liu, 2012). In Phase III (1980 – until), the Revolution and Opening-up policy gradually allows the market to take over musicals. However, human resources for musicals were lost or aged. In this Phase, Chinese people started to perceive Western culture. Under the relatively open political and social environment, musicals have the opportunity for development.

Since the policy, Chinese economy has been growing robustly and rapidly, which provides the economic environment for musicals. With the rise of globalisation and the Chinese economy, Western musicals also have been arising in the country (Kim, 2015). Kim (2015) highlights that globalisation has positive impacts on the development of Chinese musicals. Kim (2015) reveals that differences in business models, media production, consumption habits as well as cultural and political filtering are obstacles to the development of Western musicals in China. Nevertheless, with the help of expertise and technology, international musicals have reborn in China and gained great economic returns. Shanghai is widely regarded as the Chinese centre of musical venture in terms of international collaboration. The open political environment, maturing cultural markets, and Western musicals’ determination to globalisation are core factors pushing the Chinese musicals.

The Broadway musical Chicago was heavily marketed in Shanghai for the first time, in 2014. However, the performing team cancelled the show due to the poor preparation of the local theatres. Apparently, the local theatres’ technological infrastructures failed to meet the demands of the performing team (Kim, 2015). The case reflects that the Chinese theatres still are incomparable to world-class theatres in terms of technology.

Kim (2015) points out that musicals are a relatively new type of entertainment in China. However, the success of the Opera’s London team in 2013 in Shanghai proved the expansion and potential of the local theatres. Between 2005 and 2015, potential audiences of high-end entertainment have been increasing, whereas the industry’s capabilities of conducting business and using technologies also have been hindering the fast-growing demands. It is the case that the Western musical is not a completely new thing for young citizens of Shanghai. The Phantom of Opera had a performance in 2007 and drew great attention. Language obstacle hinders international musicals to gain huge success and great popularity in large cities, even though the English speakers and returnees have been increasing in China.

The development of the global musical in China requires a new entertainment model that can fully localise global musicals to adapt to Chinese audiences. Kim (2015) illustrates that Mamma Mia was the musical that was successfully localised. In 2011, Mamma Mia entered the stage of the Chinese theatres totally for 188 times in three largest cities: Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. The musical re-staged for 124 times in 2013 and planned to continue its performance. Later, another musical Cats was created and performed in 2013. The original creator in London legally permitted the continued performance of both shows. A joint venture between a Korean company CJ and the Chinese government known as The United Asia Live Entertainment (UALE) produced the two localised musicals and introduced them to the market.

Furthermore, Kim (2015) points out some essential facts about the development of the music business in China. Firstly, some cities already had a proper environment for the musical entertainment market. Even though musicals can be profitable, it is hard to ensure the successful rate. Secondly, limits to foreign musicals are much more than limits to national musicals. Thirdly, there is a gap between local musical theatres’ competencies and the requirements of international musical business. It means that local theatres’ skills and technological capabilities are unable to match global musical businesses. By international joint venture, international musical business can cover the shortage of local theatres in experience and capabilities. Two forms of musical production are worldly pervasive: 1) local productions and 2) foreign tours (Kim, 2015). In the case that locals are unable to create musicals, foreign musical tours become the only option, whereas the cultural obstacles to these tours are high. Thus, it is significant for this dissertation to deeply discuss musical theatres in a global environment.

2.3 The Challenges for Musical Theatre in a Global Environment

Global musical tours and international joint ventures can be viewed as the practices of globalisation. Foreign tours of musicals are regarded as direct exports of products and services. A deeper type of business internationalisation is to build production facilities and distribution facilities in host countries (Baltzis, 2005). For example, UALE is an international joint venture between a Korean company and Chinese government. The Korean company provides musical production technologies and management, and the Chinese partner takes responsibilities of staffing and marketing. Korean team recruited and trained human resources for musicals in the initial process, and then the Chinese partner continued to produce musicals (Baltzis, 2005). The collaboration also helped technology and knowledge transferring. UALE takes the role of cultural exchange by bringing different stories, styles, shows and technology to China.

2.3.1 Cultural Barriers

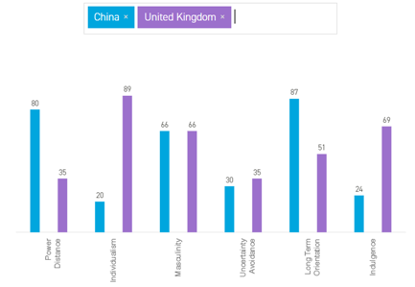

Nevertheless, the globalisation of musicals faces cultural barriers. The uniqueness of Chinese culture hinders the invasion of foreign cultural products. The Chinese culture is highly different from Western culture, based on Hofstede’s national dimensions. Thus, the Chinese consumers may be unwilling to accept foreign musical cultures.

Taking one typical western culture, British culture, for example, the cultural differences between China and the UK are significant in terms of Hofstede’s national dimensions, as the figure below shows. The two cultures are highly divergent in power distance, individualism, long-term orientation, and indulgence (Hofstede, 2011). To begin with power distance, Chinese people have greater tolerance to power which is distributed in an unequal way than British people (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005). With higher power distance, Chinese people accept people with great power having privileges and they are willing to comply with the specific orders of people with great power (Hofstede, 2010). On the other hand, British people are more willing to work under autonomy and pursue equality. As a result, more British musicals advocate equality than Chinese musicals. In the dimension of individualism, Chinese people are collectivists who rely on Guanxi (social networks) to function their society and life, so they are unwilling to hurt their relationship with others (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005). Meanwhile, face-saving is important for Chinese people to maintain their social networks. On the other hand, British people rely on laws and rules to function their society and life. In terms of long-term orientation, Chinese people focus on the future and are unwilling to risk their life (Hofstede, 2010). They maintain stronger links with its own past while addressing the challenges at present and in future than British people (Emery and Tian, 2010). They are very pragmatic and believe truth heavily depends on situation, context, and time. They have proficiency in adapting to traditions easily to altered context and the preference to save and invest to achieve results. However, British people have more spirit of adventure and focus on the present. In terms of indulgence, Chinese people have strong capability to constrict their desires and impulses. They are highly constricted resulting in cynicism and pessimism (Emery and Tian, 2010). On the opposite side of British people, Chinese people pay less attention to leisure time but strongly control their desires (Emery and Tian, 2010). Their actions are constricted by social norms. Generally, Chinese people are more willing to accept the unequal power distribution, are more involved with each other, and have a stricter social hierarchy than UK culture. Meanwhile, Chinese culture focuses on long-term benefits and issues and tries to avoid enjoying themselves.

The long cultural distance generates cultural barriers for Western musicals to expand into the Chinese market. It is highly possible that Chinese audiences are unwilling to accept the values from Western musicals. Due to these cultural differences, Chinese audiences are less likely to enjoy and appreciate Western musicals.

Figure 1: China Versus the UK, Cultural Comparison

(Source from: Hofstede-Insights, 2020)

2.3.2 Political barriers

The development of the Chinese culture industry is strongly and significantly affected by politics. Even though the Chinese government has plans to gradually relieve restrictions to the cultural industry (See Section 2.6), the conservative and obstinate ideological systems hinder the plan. More importantly, the Chinese government does not intend to fully open the cultural industry. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) dominates the state council, army, national congress, and people’s political consultative conference, which are the four major political institutions of China (Lawrence and Martin, 2013). The CCP has the absolute dominating position in all political institutions. More importantly, the CCP controls all of the media through the State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) (Lawrence and Martin, 2013). In the cultural industry, the SOEs are the forces which however are controlled by the CCP. Based on such political power of the CCP, it has strong capabilities to intervene and regulate the Chinese musical market. The CCP intentionally hinders cultural change and people to directly experience Western culture (Faure and Fang, 2008). The strong evidence is that the CCP has been blocking worldwide social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

The Chinese government is famous for its rigorous censorship system for cultural products. He (2017) studies cultural censorship systems in the cultural industry and finds that the Chinese government adopts legal institutions to strategically meet the political needs of content control and market domination. He (2017) illustrates two challenges for foreign copyright owners to do businesses in China: pervasive copyright infringement and market access. Hence, foreign musicals face the problem of Intellectual Property (IP) infringement in China, which negatively affects the profitability of foreign musicals. Secondly, the Chinese consumers are unable to access many foreign cultural products, because the government has rigorous constrictions to the importation of foreign cultural products. As a result, the Chinese consumers have constricted capabilities to access the foreign cultural products. He (2017) highlights that cultural products are strictly limited by a group of censorial regulations. The right of free speech is limited under such intensive censorship. More importantly, ambiguities in regulations and laws are threats to the expansion of foreign musicals in China. The Chinese regulations and laws have many ambiguities. The policymakers strategically adopt ambiguities to offer subordinates flexibility to enforce policies and avoid taking responsibilities for unappreciated laws and regulations (Backer, 2013). However, the ambiguities create challenges for foreign musical producers to comply with the Chinese laws and regulations. Meanwhile, the ambiguities also result in the divergences in law enforcements, which create the expansion of foreign musicals throughout China. For example, some foreign musicals can pass censorship in some regionals but are illegal in other regionals.

2.4 The Challenges for Musical Theatre in a Digital Environment

2.4.1 Youth

In the digital age, entertainment is fast diversifying and becoming increasingly richer. Younger generations are distracted by these entertainments such as social media, online video games, pop culture, electronic music and so on.

Hesmondhalgh (2005) highlights that social structure and musical type have strong influences on young generation’s musical tastes. Given that the intensive digitalisation has affected social structure and musical type, it is reasonable to deduce the impact of digitalisation on youngers’ musical tastes.

Avdeeff (2014) illustrates that technology is a mediating factor in the relationship between youth and music. With the rise of technologies, the relationship has changed significantly. At present, the ways that digital technologies integrate into social relationships restructure the way that young generations listen to and perceive meaning in music and also the way that they form their musical tastes and their actions in social situations. The argument of Avdeeff supports the impact of digitalisation on young people.

In the digital age, many factors distract young people from musical theatres:

1) Stories and characteristics of musicals are not attractive to young people;

2) Many musical theatres have no involvement into new marketing techniques and channels such as social media and their communication with young people is less;

3) Young people have busy lifestyle so that they have less time for musicals; and

4) High cost of musical theatres and high barriers discourage young people.

2.4.2 Digitalisation in Musical Theatre

Hillman-McCord (2017) studies the digitalisation in musical theatre. The study highlights that the digitalisation has essentially changed how musicals are manufactured, followed, admired, promoted, evaluated, researched, spread and casted. Digitalisation has created this unprecedented transformation (Carboni, 2015 and Gordon, 2011). Because of the business essence of musical theatre, the digitalisation in musical theatre is moving toward profitability and efficiency.

In Chinese theatre, digitalisation has made slow progress. Online theatres are rare, and they are available only for special occasions. This is because theatres are not popular and attractive in China. Traditional opera such as Beijing opera as a form of musicals are habits of older generations who have no preference for the internet (Kim, 2015).

In the UK, Arts Council England, Society of London Theatre (SOLT) and UK have tried to develop ‘Live-to-Digital’ which integrates Event Cinema, streaming and downloading online and television broadcast (Arts Council, 2016). Live-to-Digital also involves online distributions and channels, commissioners, and industry organisations, resulting in a much more complicated ecology. There are also Digital Theatre, The Space and Canvas and those individual theatres which adopt digital technologies. According to the Arts Council (2016), the Live-to-Digital has a future prospect. However, the survey conducted by Arts Council indicates that Live-to-Digital is unlikely to affect attendance to live theatres. It shows that theatre attenders do not have neither more nor less tendency to go to live theatre if they experience it by digital technologies. Those people who watch digital performances have slightly more tendency to go to live cultural performances more frequently than the average theatre audiences. Nevertheless, digital users are younger and more diverse than live theatre audiences. People do not believe that Live-to-Digital can replace live theatre and they consider it as a completely different experience. According to Arts Council (2016), 72% to 75% respondents highlight they regard Live-to-Digital as novel approaches to watching theatre. To sum up, the findings of the study of Arts Council (2016) prove that digitalisation fundamentally changed the theatres in multiple ways, which is consistent with Hillman-McCord (2017)’s argument. Meanwhile, the study also finds that digital theatres cannot replace live theatres. Even though digitalisation in the Chinese theatre has slow progress, the evidence of the UK suggests that digitalisation will not pose an intensive competition against live theatre in China.

2.5 The Audiences for Musical Theatre

2.5.1 Marketing Musical Theatre

Song and Cheung (2013) illustrate that market positioning and marketing strategy are two important variables affecting the performance of Chinese theatrical performances. Song and Cheung (2013) highlight that marketing positioning and marketing strategy include the following variables: marketing team, selling tickets on the Internet, media promotion, package tourists, travel agency and so on. To be noticed, the study focuses on theoretical performance in tourism, so it involves the marketing channels such as package tourists and travel agencies. However, the findings of the study are relevant and important to this dissertation. Marketing positioning and marketing strategy are two important methods enabling theatres to gain success in the competition.

2.5.2 The Chinese Market for Musical Theatre

The Chinese market for musical theatre is relatively thin. The musical market in China has even industrialised (Morrow and Li, 2015). Many players in the market lack effective and feasible business models. Penketh (2010) illustrates that most musicals cannot be performed in long-term because of the lack of operation and management capabilities. Another issue is the lack of theatres especially for musicals. Most musicals end after a few shows because there is no permanent theatre for them to actualise long-term performance (Penketh, 2010). Many musical theatres are built and designed specially to protect and conserve Chinese traditional opera, such as Beijing opera, Henan opera, etc., which however are not suitable for modern and Western musicals.

2.5.3 Financial Aspects of Musical Theatre

Most musical theatres are owned by the SOEs which have government funding. Profitability is not the major concern of these musical theatres. However, most of these musical theatres are not generating profits (Morrow and Li, 2015). These theatres are unlikely to support the performance of musicals in long-term because they are built for Chinese traditional opera, as mentioned. Private theatres have the purpose of profit maximum, whereas musical theatre is not their best option to maximise profits (Morrow and Li, 2015).

2.5.4 Developing New Audiences for Musical Theatre

Developing new audiences for musical theatre is an important task for developing musicals in China. However, the attractiveness of musical theatre to young Chinese generation is relatively weak (Kim, 2015).

2.6 Development Prospects of Musicals in China

2.6.1 Political factors

The Chinese government has the policies that increase the openness of the cultural market and facilitates the market. In 2007, the national congress of the CCP published its plan to facilitate ‘great cultural development and prosperity of socialism’, on the foundation of Chinese national culture and expected to be a leader of global culture (Jianfei, 2011). The globalisation of Chinese culture is a political task. The restructure of the Chinese culture industry is based on a market-economy system (Shan, 2014). The Ministry of Culture orients and regulates the restructure task by providing financial support to large SOEs such as CCTV Group, the China Arts and Entertainment Group. The task involves promoting foreign cultural partnership and cultural exchange.

According to (Shan, 2014), the plan to facilitate culture industry has the following aims:

1) To form a new development drive to change the industrial structure by supporting the culture industry;

2) To accelerate major projects and reinforce the general competitive capabilities and size of the culture industry;

3) To encourage the SOEs engaged in the cultural industry to become stock companies with a variety of forms of ownership structures;

4) To reduce obstacles to entry of foreign investments;

5) To encourage the performing arts to engage in live entertainment industry, under the supervision of the Ministry of Culture;

The development of the culture industry certainly is regulated by political institutions and strongly associated with them. As mentioned, the conservative and obstinate ideological systems constrict the openness of the culture industry. The CCP is afraid of the effect of foreign culture on political stability. Protectionism and paternalism contribute to ideological safeguards and limit the development of the culture industry and expansion of foreign cultures (Shan, 2014). Nevertheless, the development requires communication and interactions between Chinese and foreign culture industries who can bring the latest content and technology. The tight censorship and administration strongly control media and cultural products and constricts supply of foreign cultural products (Shan, 2014). The positive sign for the development of the culture industry is that the Chinese government is reducing its political monopoly imposed on culture. China is gradually untying the culture market.

2.6.2 Economic Factors

The revenue of China’s cultural industry has been steadily growing in recent years. In the first three quarters of 2019, the total revenue of the 56,000 investigated companies reached USD 882.9 billion, increasing by 7.6% year on year (China, 2019). Since 2008, the cultural industry has been supported by the government and developing rapidly, and, more importantly, it achieved great economic success (Jianfei, 2011). Jianfei (2011) highlights that cultural industries are becoming important industries in some regionals. The development of cultural industries concentrates on urban areas of the east coastal regionals, especially for Beijing and Shanghai. Moreover, the industrial structure of cultural industries is evolving rapidly (Jianfei, 2011). There is a trend that the proportion of the culture industry to GDP is increasing in many provinces, because the contribution of the culture industry to the provincial economy is increased. As mentioned in 2.6.1, the government has great commitment to develop a strong cultural industry and bring the industry the market economy-oriented reform. Since 2003, those SOEs with engagement in culture industry started to conduct gradual reform toward market-orientation (Jianfei, 2011). The culture industry organisations have to meet the needs and wants of audiences to market their products and services (Jianfei, 2011).

2.6.3 Obstacles to the Development of Chinese Musical Theatre

Jianfei (2011) illustrates the obstacles to the development of Chinese musical theatre. Firstly, the developing level of cultural industries in China is imbalanced due to the different economic foundation. The culture industry in East China is most well-developed, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and so on. Provinces in the central area of China have a second level of culture industries. Most western provinces are underdeveloped. The clusters of the culture industries are uneven. Given that the promotion of the culture industries is government-oriented, it is very easy for the different layers of the governments to lose its direction (Shan, 2014). Furthermore, the culture industry faces the problems of the lack of professional talents. The Chinese academic and education system is unable to support the requirements of the developing culture industries. Even though Chinese universities have developed many disciplines supporting culture industries at Bachelor, Master and PhD level, the industry needs creative talents, professions, and technological talents in different segments of the industry (Shan, 2014). Thirdly, lack of awareness of brand establishing hinders the development of the industry. Many domestic businesses focus on simple imitation but pay no attention to creativity. Local businesses neglect the importance of developing their creativity to generate their own intellectual properties. Meanwhile, the awareness of developing Chinese national brands is still relatively weak. Brand developing and establishing requires long-term efforts (Mackerras, 2011). Fourthly, Intellectual Property Right (IPR) protection is relatively weak in China. Chinese people have low respect for IPRs and have a strong tendency to involve in IP infringements.

There are many internal and external factors affecting the development of Chinese musicals. Song and Cheung (2013) reveal other key internal factors including storyline and performing, investment and financial support, operation and management, performing team, and marketing capabilities. Also, their study illustrates the core external factors including cooperation between cultural industries and local tourism, supporting policies, privatization, and social as well as cultural influence. Problems in these factors negatively affect the development of Chinese musicals.

MacDonald (2020) highlights that many factors hinder rapid development of Chinese musicals. Firstly, localisation of foreign musicals is difficult. Translation is only one of the challenges. Musicals themself are exported from western countries. Secondly, lack of funding supports also impedes the development of musicals. Except for Broadway’s musicals, it is hard for the Chinese musicals to gain profits. Even though the Chinese government has financial support to the culture industry, its financial support to musicals are rare and its concern to musicals are very less (Mackerras, 2011). Thirdly, the shortage of talents and professionals result in the difficulties of developing musicals. In China, the education for musical professionals and talents concentrates on universities and colleges, whereas musical education in elementary and secondary school is weak. As a result, the talents for musicals are neglected. More importantly, a large proportion of the talents chose to work overseas and shift their careers to TV plays. The Chinese musical industry lacks talents who can focus on the implementation of original works and the sustainability of musical development (Mackerras, 2011). In China, there are artists and investors, whereas the market lacks those people who can take responsibility for linking script development, investing, performers management, production team and marketing (Mackerras, 2011). Another problem of the musical industry is the high tickets. The causes of the high-priced ticket issue include high production costs, high rental costs, multiple agencies of ticket sales, and free tickets. Free ticket is a latent rule that local authorities and agencies require musical holders to provide free tickets, which however will increase the costs of the musical holders. The average ticket price of the Chinese musicals is much higher than that of musicals in Japan and western countries. Furthermore, the originality of the Chinese musicals is low. The lack of capabilities exists in many aspects including compose, choreography, the storytelling and performance. Many musicals have no live music performance and live band. Many of the choreography overly focuses on creating a large scene and individual dancing technique, but they separate from the story and ignore the importance of conflicts in drama (Mackerras, 2011). The stories are highly routine and make the audience feel bored. There are very few musicals which can maintain long-term performance. Many musicals were stopped after a few performances, which can be explained by underperformance of these musicals and/or by the lack of theatres for their long-term performance. Thus, it is hard for the Chinese musicals to achieve industrialisation. Additionally, there has not been a complete industry chain for musicals and a large scale of markets for musicals.

MacDonald (2020) illustrates that Chinese millennials have enthusiasm from Western musicals. They have been receiving western values and cultures during their growth-up, who are different from their parents.

2.7 Summary

This chapter discusses the topic of theatre and its marketing. Based on the history of Western musicals, the chapter finds that the development of musicals needs pioneers and experimenters such as excellent composers and librettists. The history of musicals during World War One suggests that political context has a relationship with the development of musicals. The development of musicals is strongly associated with the economy and technologies. These factors also are important for the Chinese musical market. Then, the chapter discusses the challenges for musical theatres in a global environment. It finds that globalisation of musicals faces cultural barriers. Chinese culture is highly differentiated from Western culture, making importing of foreign musicals difficult. Even though the Chinese government has plans to gradually relieve restrictions to the cultural industry, the conservative and obstinate ideological systems hinder the plan. Digitalisation is not a significant threat to the Chinese musical theatres, based on the case of the UK. Even though digitalisation in the Chinese theatre has slow progress, the evidence of the UK suggests that digitalisation will not pose an intensive competition against live theatre in China. The chapter furtherly studies the audiences for musical theatres. It finds that these theatres are weak in marketing and financial aspects. The Chinese market for musical theatre has not matured yet and it is hard for musical theatre to develop new audiences.

In the last section, the chapter discusses development prospects of musicals in China. The positive political sign for the development of the culture industry is that the Chinese government is reducing its political monopoly imposed on culture. China is gradually untying the culture market. The revenue of China’s cultural industry has been steadily growing in recent years. Since 2003, those SOEs with engagement in culture industry started to conduct gradual reform toward market-orientation. However, government intervention has less concerns on musicals. There are many barriers to the development of the Chinese musical theatres. The developing level of cultural industries in China is imbalanced due to the different economic foundation. The culture industry faces the problems of the lack of professional talent. Lack of awareness of brand establishing hinders the development of the industry. IPR protection is relatively weak in China. Many key internal and external factors affecting the industry. Internal factors include storyline and performing, investment and financial support, operation and management, performing team, and marketing capabilities. The core external factors include cooperation between cultural industries and local tourism, supporting policies, privatization, and social as well as cultural influence. Localisation of foreign musicals is difficult. Lack of funding supports also impedes the development of musicals. The shortage of talents and professionals result in the difficulties of developing musicals. Another problem of the musical industry is the high tickets. The lack of capabilities exists in many aspects including compose, choreography, the storytelling and performance. It is hard for the Chinese musicals to achieve industrialisation.

Chapter Three – Methodology

3.1 Introduction

This chapter justifies the choices of research methodologies in the dissertation. The dissertation used both quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative data was collected by questionnaires, while interviews were used to collect qualitative data.

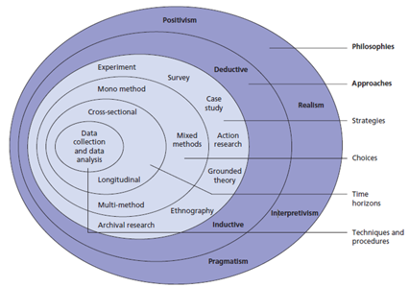

Figure 2: Research Onion

(Source: Saunders and Lewis, 2012)

3.2 Descriptive Research

Myers (2008) illustrates that descriptive research has the purpose to illustrate current issues by data collection and analysis allowing researchers to generate complete and specific descriptions. This dissertation adopted descriptive research to illustrate characteristics of the development prospects of the Chinese musicals markets by focusing on the case of ‘On Leaving Cambridge Again’. Ethridge (2004) highlights that a descriptive study can be viewed as a simple approach to describe, decide and identify analytical study targeting to build how it came to be. Through descriptive research, this dissertation can describe and identify the development prospects of the Chinese musical markets.

This dissertation did not adopt exploratory research. This is because such research focuses on the identification of the research questions and has no intention to provide conclusive solutions to problems. Exploratory research is suitable to identify a problem which has not been identified explicitly yet (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2012). On the other hand, causal research, also known as explanatory research, targets to explain cause-and-effect relations (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2012). This dissertation had no intention to identify cause-and-effect relations but emphasises on the description of the developmental prospects of the Chinese musical markets. Thus, both exploratory research and causal research are not suitable for this dissertation.

3.5 Case Study

Case study was used as the research strategy in this dissertation. It focuses on an extremely small sample size to analyse a phenomenon. Case study allows researchers to analyse both qualitative and quantitative data related with the context of research phenomenon and to study complexities of real-life situations. By case study, this dissertation analysed quantitative data from questionnaires and qualitative data from interviews (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2012). Case study enables researchers to generate in-depth findings and understanding about the developmental prospects of the Chinese musical markets. Through descriptive case study, this dissertation analysed the sequence of interpersonal events. It specifically described the developmental prospects of the Chinese musical markets. The case study of the dissertation was ‘On Leaving Cambridge’, a famous musical in China. By case study, the dissertation explored out in-depth findings for the Chinese musical market (Collins, 2010). Case study is an economical research strategy for student-conducted research. However, it is important to realise the limitations of case study. Case Study has a shortage in generating universals because of its limited representative. It is criticised for its lack of rigour, issues in data analysis. Case study is weak in identifying cause-effect relationships, but this dissertation has no intention to identify any cause-effect relationship. Positivists criticise that case study refers to a subjective method rather than objective method. However, this dissertation combined both qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis to generate reliable findings.

This dissertation chose ‘On Leaving Cambridge’ as the case because this musical was representative and famous in China. The musical ‘On Leaving Cambridge’ was performed and adapted by many parties. Due to the popularity of the love story and poetry, it is relatively familiar for Chinese people in comparison to other musicals.

Survey is not suitable for this research. Even though it is effective to collect quantitative data, it has no advantage of collecting qualitative data (Littlejohn and Foss, 2009). More importantly, survey is more consistent with positivism philosophy and survey is a quantitative approach, which has less support for qualitative data (Littlejohn and Foss, 2009). It may be weak in generating in-depth findings, so it is not suitable for this dissertation. On the other hand, observation is also not suitable for this dissertation, which is time-consuming and costly.

3.6 Cross-sectional Time Horizon

Cross-sectional time horizon was appreciated for this dissertation. This dissertation only collected primary data for once (Bryman and Bell, 2015). It had no plan to make a historical comparison, so it was not necessary for the researchers to collect primary data more than once. Longitudinal time horizon is not suitable for this dissertation, because it collects primary data several times. However, this dissertation had to be completed within a limited time, so it had no time to apply a longitudinal time horizon.

3.7 Questionnaires

This dissertation adopted questionnaires as the data collection technique for quantitative data. Questionnaire is viewed as the most effective tool to collect a huge amount of quantitative data from a huge sample size (Bryman and Bell, 2015). Researchers take advantage of questionnaires to build a large quantitative sample size in a fast way. More importantly, questionnaires are economical and affordable for students. By a website, researchers can easily spread questionnaires and restore data. The website can automatically collect data, meanwhile researchers can focus on other research tasks. Even though the process of designing questionnaires can be time-costly, the data collected by questionnaires can be easily analysed statistical software (Bryman and Bell, 2015). Questionnaire can effectively quantify data.

This dissertation used a website to spread the questionnaires – www. wjx.cn. By this website, the researcher easily spread questionnaires and restore data. The researcher shared the links of the web site to Chinese social media to access potential participants. Furthermore, all questions in the questionnaire are close-ended, which is convenient to quantify their answers.

To be noticed, questionnaires have their own limitations. Firstly, not all answers of the participants can be quantified into numerical form, particularly in social research (Monette, Gullivan and DeJong, 2010). Secondly, some participants could fulfil questionnaires in an irresponsible way, thus compromising the validity of the dissertation (Monette, Gullivan and DeJong, 2010). Thus, this dissertation used a consent letter appealing its participants to answer the questionnaires in a responsible manner. Another issue of questionnaires is that some participants may have misunderstandings about the question, so they provide unreliable answers. This dissertation devised simple and clear questions to minimise misunderstanding. Due to the limitations of questionnaires, this dissertation also adopted interviews to collect qualitative data.

3.8 Interviews

Interview is an effective approach used to collect qualitative data, which is implemented in this dissertation. Interview means intensive individual conservation to find out a small number of respondents’ viewpoints toward a situation (Albery and Munafo, 2008). By conservation, interviews enable respondents to have two-way communications with respondents. It means that the researcher can explain the research questions and ask further questions and personalised questions during the conservations. Thus, interviews can cover the limitation of questionnaires that cannot allow researchers to explain questions to participants. More importantly, respondents are unlikely to lie during face-to-face interviews. By a face-to-face context, researchers can observe the facial expression and responses of respondents to evaluate their answers (Albery and Munafo, 2008). Interview is consistent with interpretivism, which also aligns with realism philosophy. Moreover, interviews allow researchers to collect specific and deep data. By fully involving the data collection process, these researchers can clarify some issues within the data.

To be noticed, interviews require researchers to have good communication, questioning and listening skills (Polonsky and Waller, 2011). The researcher of the dissertation had the competencies to conduct interviews. Even though interviews can be time-costly, this dissertation interviewed only five respondents. Thus, the researcher had sufficient time to conduct interviews. However, interviews cannot effectively collect quantitative data. Hence, this dissertation also adopts questionnaires to collect quantitative data.

This dissertation conducted face-to-face interviews in public areas. The researcher waits for the end of ‘On Leaving Cambridge’ at FengChao Theatre Beijing and then found volunteers who were willing to provide information. The researcher found musical fans who expected the development of the Chinese musicals. Each interview costed 10 to 12 minutes. The researcher adopted semi-structured interviews. It means that the researcher asks a group of designed questions and then ask additional question based on each respondents’ responses. Semi-structured interviews allowed researchers to have high flexibility to dig out deep information.

3.9 Research Population and Sample Size

The research population was those Chinese musical fans, enthusiasts, and workers of the industry, who has deep understanding or sufficient experiences in the industry. In other words, the research covered workers and audiences of the Chinese musicals to have a comprehensive understanding about Chinese musicals. For fans and enthusiasts, the dissertation only accessed those who have over 5 years history of attending Chinese musicals. For the workers, the dissertation chose to collect data from those who have been working in the industry for over 5 years.

The sample size is 160 questionnaires and 5 interviews including 3 fans and enthusiasts and 2 workers.

3.10 Sampling Approach

Self-selection sampling technique was implemented in this dissertation. The technique, as a non-probability sampling technique, enabled researchers to effectively build a large sample size in a fast way (Monette, Gullivan and DeJong, 2010). Any people who meet the standard can participate in the dissertation. Furthermore, by self-selection sampling technique, the researchers can collect data from who voluntarily participate in the research (Polonsky and Waller, 2011). Because they are not motivated by financial rewards but by their willingness, they are more likely to provide reliable data.

However, the self-selection sampling technique has low representativeness (Polonsky and Waller, 2011). As the countermeasure, this dissertation collected a relatively large sample size to improve representativeness. More importantly, the dissertation adopted case study which does not require large representativeness.

On the other hand, profitability sampling techniques such as random sampling techniques cannot be used in this dissertation, because the researcher is unable to build a sample frame that contains all people who ever attended the musical, ‘On Leaving Cambridge’. Without the sample frame, the research cannot ensure that it can access to each audience of the musical with the same possibility (Monette, Gullivan and DeJong, 2010). In the comparison of other non-probability techniques, self-selection sampling can collect in a faster way. To complete data collection within limited time, it is reasonable for this dissertation to use self-selection sampling to collect data.

3.11 Reliability and Validity

To ensure the reliability of the research, this research ensured the reliability of theories and knowledge used in the literature review. It only collects and analyses the knowledge and theories from convincing journals and books. The researcher also adopted a strict objective viewpoint to deduce results and avoided personal biases.

3.12 Research Ethics

This dissertation adopted a consent letter to inform potential respondents the purpose and aim of the research and make them understand what kind of questions would be asked during the research. The consent letter also illustrated respondents’ rights. They had the right to withdraw from this research before the researcher completes the data analysis. This research involved no deception and it is honest and directly illustrates its purpose and aims. The researcher did not plan to provide debriefing to participants. To protect participants and respondents, the research recorded and asked no private information about them including name, contacts, etc. This dissertation was confidential, and the data and results would only be accessible for the University. The researcher complied with the University’s policy of data collection.

3.13 Summary

This dissertation conducted a descriptive research in accordance with realism philosophy that supports both quantitative and qualitative analysis. It adopted deductive approach rather than inductive approach. Case study was used as the research strategy in this dissertation. By case study, this dissertation analysed quantitative data from questionnaires and qualitative data from interviews. Cross-sectional time horizon was appreciated for this dissertation. This dissertation only collected primary data for once. This dissertation adopted questionnaires as the data collection technique for quantitative data. Interview was an effective approach used to collect qualitative data, which was suitable for this dissertation. The research population was those Chinese musical fans, enthusiasts, and workers of the industry, who had deep understanding or sufficient experiences in the industry. The sample size was 160 questionnaires and 5 interviews including 3 fans and enthusiasts and 2 workers. Self-selection sampling technique was implemented in this dissertation. The technique, as a non-probability sampling technique, enabled researchers to effectively build a large sample size in a fast way. The research strictly complied with ethical codes of social research.

Chapter Four – Findings

4.1 Introduction and background to the case study

This section analyses the findings of the questionnaires and interviews respectively.’. Then, it discusses the findings from the different sources.

‘On Leaving Cambridge’ is an important and famous musical in China, which has aroused significant and profound influence. It is viewed as a Chinese classic musical and has been played by many artists. The musical is adapted based on the poetry which has the same name.

‘On Leaving Cambridge’ is a poetry wrote by a famous poet, Hsu Chil-mo (1987 – 1931) who graduated from Clark University in the US, Columbia University, and Cambridge University and was proficient in banking, economy and political economy. He only took 10 months to graduate from Clark University and became a professor of Peking University when he was 27 years old, who was a genius. The poetry describes the emotions and feelings of Hsu Chil-mo when he was preparing his emotions to leave Cambridge. The poetry was very romantic that expressed his feelings that did not want to leave Cambridge, but he had to, so he wanted to watch it again. Hse was a very influential man in modern history of China. Now, Chinese people are still obsessing with the talents of Hse. His painting is considerably expensive and each of his top 10 paintings is worthy of over £9 million, singly.

However, the musical ‘On Leaving Cambridge’ describes a complicated love story between Hsu Chil-mo, his wife, his friends, and the girl he obsessed. Liang Si Cheng and Lin Hui Yin were a young couple who committed to devote themselves to architecture and come to the US for the pursuit of their love. However, Hsu Chil-mo has been obsessing with Liang Si Cheng and was schoolmate of Lin Hui Ying when they were studying in Cambridge. So, Hsu Chil-mo constantly recalled his memory of sharing the view of Cambridge with Lin. However, Lin married Xu Zhi Mo who was the friend of Hsu in Canada. Then, Hse married Lu Xiao Man who however indulged in the night life and modern life of Shanghai and did not want to come to Perking to live with Hse. When Lin was ill, Hse visited her and recalled the precious memory of studying in Cambridge. The marriage of Hse and his wife fell into trouble. Then, Lin heard the tragedy that Hse died in airplane accidents. Lastly, Xu, Liang, Lin and Hse’s wife sang the song ‘On Leaving Cambridge’.

The musical ‘On Leaving Cambridge’ was performed and adapted by many parties. Due to the popularity of the love story and poetry, it is relatively familiar for Chinese people in comparison to other musicals. In 2001, the musical was firstly adopted by a professor of Chinese Conservatory of Music and performed in a small theatre in Beijing. The musical focused on acting skills of actors rather than magnificent stage and music. The language of the musical used is simple for everyone. To be noticed, there are many versions of ‘On Leaving Cambridge’ in China. The musical was performed in China's grand national theatre in 2009 for the first time. To fit in the large stage of the threat, the musical was re-programmed.

4.2 Data Analysis of Questionnaires

This research totally collected 154 questionnaires and the data analysis is shown in the below.

4.3.1 Demographics Analysis

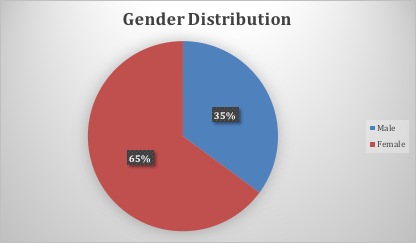

There are 100 female participants accounting for 64.9% of the total population and 54 male accounting for 35.1%. It reflects that female audiences may be larger than male in Chinese musical market.

Figure 1: Gender distribution

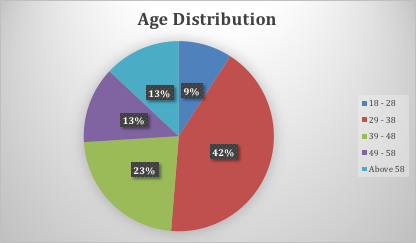

As Table 2 shows, the largest age group is ’29 to 38 years old’ accounting for 42.2%, followed by ’39 to 48 years old’ (22.7%), ’49 to 58 years old’ (13.0%), ‘Above 58 years old’ (13.0%), and ’18 to 28’ (9.1%). This age distribution suggests that the largest age of audiences in Chinese musical market is 29-to-38-year olds, followed by 39-to48-year olds.

Figure 2: Age Distribution

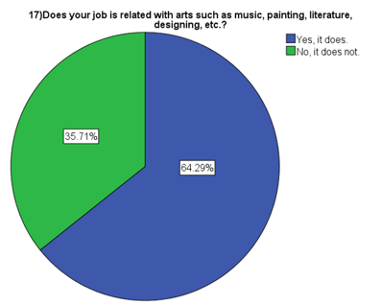

The research finds that 64.3% of musical lovers in China have a job related to arts such as music, painting, literature, designing, etc. This suggests that these populations are more likely to be interested in musicals.

Figure 3: Job’s Relevance to Arts

Overview of Demographics of Participants

|

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Gender Distribution |

Male 54 Female 100 |

Male 35.1% Female 64.9% |

|

Age Distribution |

18 – 28 (14) 29 – 38 (65) 39 – 48 (35) 49 – 58 (20) Above 58 (20) |

18 – 28 (9.1%) 29 – 38 (65%) 39 – 48 (35%) 49 – 58 (20%) Above 58 (20%) |

|

Does your job is related with arts such as music, painting, literature, designing, etc.? |

Yes, it does. (99) No, it does not. (55) |

Yes, it does. (64.3%) No, it does not. (35.7%) |

Table 1

Most of participants (89.1) watch musicals more than once a year. 27.3% of participants watch musicals once to twice in a year, followed by 3 – 4 times in a half year (23.4%), above 6 times in a half year (22.1%), and 5 – 6 times in a half year (18.2%). This means that most participants have enough knowledge and experience to offer their data to this research and they can offer meaningful data.

|

How often do you watch musical in China? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Above 6 times in a half year |

34 |

22.1 |

22.1 |

|

|

5 - 6 times in a half year |

28 |

18.2 |

40.3 |

||

|

3 – 4 times in a half year |

36 |

23.4 |

63.6 |

||

|

1 – 2 times in a half year |

42 |

27.3 |

90.9 |

||

|

Once a year |

14 |

9.1 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

32.5% of participants watched the musical because they love musicals, while 24.0% of participants knew the poetry and 16.9% of participants because they were interested in the love story. This means that they were attracted by the reputation of Hse Chih-mo rather than musicals. 12.3% of participants watched the musical because of their friends’ invitation.

|

Why do you watch ‘On Leaving Cambridge’? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

I know the Hsu Chih-mo’s poetry. |

37 |

24.0 |

24.0 |

|

|

I am interest in Hsu Chih-mo’s love story. |

26 |

16.9 |

40.9 |

||

|

I heard the good reputation of the musical. |

22 |

14.3 |

55.2 |

||

|

My friends invited me. |

19 |

12.3 |

67.5 |

||

|

I love musicals. |

50 |

32.5 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

Table 2

37.0% of participants are unsatisfied with the stage effect of the musical, followed by song effect, story, actors and actresses themselves, and the performance of actors and actresses. Song and stage effects are related with infrastructure and song effects alone are related with live bands. A large proportion of participants are unsatisfied with

|

What make you disappointed when you are watching ‘On Leaving Cambridge’ or other Chinese musicals? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

The performance of actors and actresses. |

15 |

9.7 |

9.7 |

|

|

Actors and actresses themselves |

7 |

4.5 |

14.3 |

||

|

Song effect |

42 |

27.3 |

41.6 |

||

|

Stage effect |

57 |

37.0 |

78.6 |

||

|

The story is too old |

33 |

21.4 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

33.1% of participants expected better actors and actresses. 26.0% of participants highlighted that they expect better song effect in this musical, followed by better song effect (22.1%) and novel story (18.8%). This suggests that the audiences expect the musical to have actors and actresses, song effect, stage effect, and novel strong.

|

What elements do you want to see in this musical? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Better actors and actresses |

51 |

33.1 |

33.1 |

|

|

Better Song effect |

40 |

26.0 |

59.1 |

||

|

Better stage effect |

34 |

22.1 |

81.2 |

||

|

Novel story |

29 |

18.8 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

Table 3

32.5% of participants expect better actors in actresses in all Chinese musicals, followed by better song effect (28.6%), better stage effect (17.5%), and novel story (21.4%). This suggests that they may not be very satisfied with actors and actresses, song effect, story and stage effect in Chinese musicals.

|

What elements do you want to see in all Chinese musicals? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Better actors and actresses |

50 |

32.5 |

32.5 |

|

|

Better Song effect |

44 |

28.6 |

61.0 |

||

|

Better stage effect |

27 |

17.5 |

78.6 |

||

|

Novel story |

33 |

21.4 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

Table 4

Over half of participants (52.6%) believe that Chinese musicals need to improve story and script. 30.5% of participants highlight that these musicals should have live music. 8.4% of participants reveal the necessity to improve theatre infrastructure. Another 8.4% of participants underline the importance to improve actors and actresses.

|

Which part of Chinese musicals you think they should improve? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Actors and actresses |

13 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

|

|

Theatre infrastructure |

13 |

8.4 |

16.9 |

||

|

They should have live music |

47 |

30.5 |

47.4 |

||

|

Story and script |

81 |

52.6 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

Table 5

32.5% of participants are very unsatisfied with infrastructure for musicals, followed by 18.2% (unsatisfied). Only a small portion of participants were satisfied or very satisfied with the infrastructure. Thus, Chinese musical industry needs to improve infrastructure.

|

What is your opinion about infrastructure for musicals in China? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Very unsatisfied |

50 |

32.5 |

32.5 |

|

|

Unsatisfied |

28 |

18.2 |

50.6 |

||

|

It is hard to say |

37 |

24.0 |

74.7 |

||

|

Satisfied |

29 |

18.8 |

93.5 |

||

|

Very satisfied |

10 |

6.5 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

Table 6

A large portion strongly agree (37.7%) or agree (37.0%) that they will watch more Chinese musicals if they have a better theatre and infrastructure. This finding is consistent with the above finding, suggesting the importance of improving theatre and infrastructure.

|

How much do you agree that you will watch more Chinese musicals if they have a better theatre and infrastructure? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Strongly disagree |

9 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

|

|

Disagree |

11 |

7.1 |

13.0 |

||

|

Neutral |

19 |

12.3 |

25.3 |

||

|

Agree |

57 |

37.0 |

62.3 |

||

|

Strongly Agree |

58 |

37.7 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

Table 7

Over half of the total participants indicate that they will watch more Chinese musicals if actors and actresses are better. 29.2% of the total participants who strongly agree with the statement. This means that actors and actresses are important variables.

|

How much do you agree that you will watch more Chinese musicals if their actors and actresses are better? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Strongly disagree |

10 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

|

|

Disagree |

6 |

3.9 |

10.4 |

||

|

Neutral |

13 |

8.4 |

18.8 |

||

|

Agree |

80 |

51.9 |

70.8 |

||

|

Strongly Agree |

45 |

29.2 |

100.0 |

||

|

Total |

154 |

100.0 |

|

||

Table 8

Large portion agree (40.3%) and strongly agree (27.3%) that they will watch more Chinese musicals if their story is new and novel. This implies that Chinese musicals should improve their story and script.

Table 9

A live band in a musical will attract more audiences to watch. 40.3% strongly agree and 26.6% agree that they will watch more Chinese musicals if they have a live band. This suggests that it is necessary for Chinese musicals to use live bands.

|

How much do you agree that you will watch more Chinese musicals if their story is new and novel? |

|||||

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Strongly disagree |

19 |

12.3 |

12.3 |

|

|

Disagree |

5 |

3.2 |

15.6 |

||