Harley Davison’s Expansion in Thailand

Executive Summary

The purpose of this research is to critically analyse international expansion and internationalisation of HD by discussing its entry mode, internationalisation strategy, and entry barriers so as to make recommendations to this company. This research finds that HD’ expansion fits its overall internationalisation strategy. More importantly, the company has been developing its capabilities and knowledge for internationalisation. It has enough understanding on Asian culture to solve cultural barriers. Secondly, the company has the following motives to develop manufacturing facilities in Thailand, including lower labour costs, more natural resources, and loosen enforcement of environmental and labour laws. With its operational capabilities, the company has locational, operational and internationalisation advantages. More importantly, HD is urgent to develop its international presence and open-up Chinese market to relieve the pressure from the declining domestic sales. By building manufacturing facilities in Thailand, the company can bypass China’s high tariffs thus improving its competitive advantages and reducing costs in the country. It seeks resources, market, efficiency and networks. H-D was motivated by its competitors’ intensive internationalisation process. Also, it has to exploit international market to cover its declining revenue in domestic market so as to ensure its sustainability. H-D’s internationalisation process fits Uppsala model. This research predicts that H-D can have a great prospect in Asia because its expansion in Thailand, as it has sound experience and cultural capabilities and great commitment to localisation.

2.1 Motives of Internationalisation

2.5 Global Value Chain and Value Chain

3.0 Internationalisation Process of H-D

3.1 The History of HD’s Overseas Investment

3.2.1 Export via Agency (Dealership)

3.2.3 Wholly Owned Subsidiaries

3.2.4 Motives of H-D’s Internationalisation

4.1 Rationale, Activities, Position in value-chain, Prior Exports

4.1.1 Motives of Entering Thailand

4.2 Global Value Chain and Value Chain

4.4 Partners in this International Expansion

1.0 Introduction

Harley Davison (HD) is an American iconic motorcycle brand founded in 1903, with over 100-year history. It has been one of two major US motorcycle manufacturers who had survived from the Great Depression. H-D has overcome many hardships including numerous ownership change, economic depressions, and intensive global competition. It is one of the largest motorcycle manufacturers with iconic brand with a large number of loyal followers. Unlike other motorcycle brands, H-D has its own differentiated culture, owner clubs and culture globally.

The company manufactures its products in the following factories: York, Pennsylvania, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Kansas City, Manaus (Brazil), Bawal (India) and Thailand. It adopts licenses, joint venture and green investment to implement its internationalisation.

With the continuous decline in the sales in the US and the intensive trade war between the US and China, the company determined to exploit Chinese market and Asian market by expanding into Thailand. The plan was to take advantages of ASEAN trade zone to avoid high tariff of China and of low labour costs in Thailand. Meanwhile, the company closed its plant in Kansa city and moved its manufacturing to Thailand in 2019 (Schuyler, 2019) reducing domestic job opportunities, on the opposite of Trump’s policy of bringing jobs back to USA. As the result, the expansion was arguable.

The purpose of this research is to critically analyse international expansion and internationalisation of HD by discussing its entry mode, internationalisation strategy, and entry barriers so as to make recommendations to this company.

Research question:

1. What is the entry mode of HD in Thailand?

2. How does HD’s entry strategy in Thailand fit with its overall internationalisation strategy?

3. How does HR overcome its entry barriers?

H-D uses its Thai plants as a breaking point to largely and fast expand in Asia by taking advantage of lower prices and higher level of localisation. H-D’s internationalisation process fits Uppsala model: it started with exporting via agency (dealership), shifted to joint venture, moved to leased manufacturing facilities and finally switched to wholly owned manufactures. It has been developing its capabilities and knowledge for internationalisation. It seeks resources, market, efficiency and networks in Thailand. With its operational capabilities, the company has locational, operational and internationalisation advantages, which allows it to use green investment as its entry mode to build its own manufacturing facilities. Green investment allows H-D to strictly control quality, manufacturing process, production schedule and output to effectively response Asian market. The strategic fit of its Thai expansion is high. H-D can achieve high level of localisation and responsiveness to Asian market and develops its business network. This research predicts that H-D can have a great prospect in Asia. Its Thai plats can largely reduce costs and its partnership with Qianjiang can improve customer satisfaction and cultivate younger riders.

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Motives of Internationalisation

A company involves into internationalisation due to a variety of motives including resource-seeking, marketing-seeking, strategic resource-seeking, and network-seeking (Dunning, 2000).

Market seekers are motivated by customer demands. They realise the significance of reaching certain target markets abroad and the importance of directly presenting internationally, so they are motivated to access these markets. Meanwhile, marker seekers also refer to those companies that invest in a specific country or region with the purpose to supply products. Dunning (1993) reveals that some companies expect to grow their markets and then increase profits. Developing physical presence in leading markets where have their core competitors may be a part of their global manufacturing and marketing strategy (Calof and Beamish, 1995). Furthermore, some market seekers are motivated by incentives such as subsidised labour (Calof and Beamish, 1995). Harris and Wheeler (2005) reveal that developing countries offer beneficial policies to attract international entrepreneurs. Furthermore, Dunning (2000) argues that some companies decide to engage in international market because their competitors aggressively expand globally. These competitors can collect a considerably large amount of revenue so as to grow their competencies against these companies (Dunning, 2000). Thus, it is critical for these companies to compete with their rivalries in all markets.

Resource seekers mean those companies which invest abroad to gain desirable resources including lower comparative costs and the resources which are not available in the home country (Oviatt and McDougall, 2005). These desirable resources include low-cost and unskilled labour, and companies use these resources to achieve cost minimisation. Resource-seeking as a motive of MNCs is associated with the pollution haven hypothesis that MNCs in developed countries move their manufacturing facilities to developing countries where have loose enforcement of environmental and employment laws (Levinson and Taylor, 2008). Large manufacturers seek the most cost-effective place for both resources and labours when they invest in overseas (Levinson and Taylor, 2008). Developing countries have loosen environmental law enforcement and cheaper labour (Birdsall and David, 1993), which allow MNCs to gain localisation advantages in OLI model.

Efficiency seekers are those companies which conduct internationalisation to maximise efficiency. Some of them expect to improve economies of scale and reduce risks (Oviatt and McDougall, 2005). By expanding into foreign markets, these companies relieve risks from cultures, institutional arrangements, economic and political environment (Yip et al., 2000). To avoid the risks caused by relying on one market, many companies choose to expand into other countries, and these risks can be changes in political and/or economic environment (Yip et al., 2000). Also, expanding into foreign market allows a company to avoid their saturated and declining domestic market, improve sustainability and achieve growth (Dunning, 2000).

Network seekers refer to those companies that implement internationalisation to develop their networks (Kingsley and Edwards, 2004). These networks can be partnership, alliances, collaboration, and other business connections. Chen et al. (2004) explain that MNCs develop networks for two reasons. Firstly, they expect to foster efficiency by engaging in a more diversified network that offers more opportunities (Yeoh, 2000). The second reason is to rise effectiveness so as to improve profitability (Chen et al., 2004). A stronger relationship with partners helps company to increase profits. Lavie (2006) illustrate that companies can gain resources from alliances and networks.

2.2 Uppsala Model

Uppsala model illustrates a company’s process of gradually strengthening their activities in foreign markets (Johanson and Vahlne, 2009). It suggests that companies gradually increase their commitment and involvement in global market. They should firstly expand into those countries which are geographically and culturally close to their home market and then gradually engage in those countries which are geographically and culturally far with their home market. Uppsala model, based on learning curve theory, describes the internationalisation process of an MNC (Forsgren, 2015).

Psychic distance refers to a set of variables disturbing the flow of information between the company and its target market (Ciszewska-Mlinaric and Trapczyniski, 2016). It causes barriers to the process of learning about and understanding a host country. Meanwhile, psychic distance refers to uncertainty caused by cultural differences and other variables hindering learning and running businesses in foreign countries (O’Grady and Lane, 1996). Johanson and Vahlne (1977) illustrate that psychic distance refers to differences in language, culture, political environment, education, industrial prosperity and so on. Boyacigiller (1990) explains that psychic distance includes the differences in religions, business communication, government, economic environment, and openness to immigration. Evans et al. (2000) further explain that psychic distance is related with marketing infrastructure, business practices and industry structure. Cross-cultural issues have strong impacts on a company’s international expansion (Ryans et al., 2003). In Uppsala learning theory, a company needs to collect and grow its international experience and theory before expanding into those countries with longer cultural distance (Johanson and Vahlne, 1990). Cross-cultural issues also are strong entry barriers to high expansion performance. Due to the cultural impacts, companies tend to adopt an adaptation or the integration of standardisation and adaptation approach (Ryans et al., 2003).

Johanson and Vahlne (1977) elaborate the internationalisation model: a MNE’s internationalisation is related with its market knowledge and commitment in a host country. The MNE’s market knowledge determines its commitment decisions which affect its current activities. Current activities have impacts on market commitment which in return is related with market knowledge. The increase in market knowledge and commitment encourages the MNE to enlarge its current activities. In return, more activates in host country help the MNE to gain more market knowledge (Blomstermo and Sharma, 2003).

Figure 1: Internationalisation Process

(Source: Blomstermo and Sharma, 2003)

Johanson and Vahlne (2009) propose a new framework describing MNE’s internationalisation process. It recognises the importance of business network and the link between the network and relationship. MNEs can cover its weakness of lacking market knowledge by developing networks and then gaining the knowledge from partners. To expand in host country, they facilitate business networks and depend on networks. Through developing relationship commitment, MNEs absorb knowledge from networks.

Figure 2

According to Hollensen (2007), Uppsala model classifies four different phases of internationalisation. When an MNE penetrates into a foreign market, it starts with non-regular export, shifts to export via agency, then builds sales subsidiary in host country, and finally achieves manufacturing in host county.

1) Phase 1: no regular export

2) Phase 2: export via agency

3) Phase 3: sales subsidiary in host country

4) Phase 4: manufacturing in host country

Uppsala model’s major purpose is to address cross-culture issues that negatively affect internationalisation of MNCs. Cross-cultural issues cause the differences in customers’ needs, wants, value, opinion, attitude, perception and communication styles (Antunes et al., 2013). Each culture is unique that has its own value, whereas cross-culture communication tends to face the issues of conflicting values (Beguelsdijk et al., 2017). More importantly, cross-culture communication can arouse misunderstanding, ineffective communication and conflicts (Beguelsdijk et al., 2017). This means that marketers have to develop localised marketing activities to fit in local culture while localisation may compromise consistency of a global brand. This is related with standardisation / localisation strategy (Rao-Nicholson and Khan, 2016). The extent of implementing standardisation / localisation strategy is critical for a MNC’s performance while it is associated with the MNC’s cultural knowledge about a host country.

Furthermore, cross-cultural issues also challenge a MNC’s management especially its relationship with local employees (Darley et al., 2013). These issues cause the differences in leadership/management style, organisational climate and atmosphere, employee-manager relationship and work style (Ekerete, 2001). Therefore, subsidies may be different with their HQ in the above aspects. It is challenging for the HQ and expatriates to properly address these differences especially when they have less cultural knowledge.

2.3 Entry Mode

2.3.1 OLI Model

OLI model (Eclectic paradigm) considers three types of advantages to determine entry mode, and the three advantages include ownership, location, and internalisation advantages (Dunning, 2000).

Ownership advantages mean the competitive advantages of a company to involve in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Robust competitive advantages empower MNEs to develop production infrastructures in an international market (Dunning, 2000).

Location advantages mean the advantages of a foreign country contributing to the company’s value adding activities. Locational attractions such as natural and immobile resources are important for an MNE to sustain its competitive advantages and enhance its value-adding activities (Dunning, 2000). If an MNE perceives that a foreign country has locational attractions, it is more likely to use FDI as entry mode.

Internalisation advantages mean the benefits for a company to internally develop products (Dunning, 2000). Those MNE which possesses advantage of operating production tasks by itself, it is more likely to adopt FDI.

2.3.2 FDI

Through FDI, an MNC generally adopts two entry modes to penetrate a foreign market, including greenfield investment and acquisitions. Green investment is to build a new wholly owned subsidiary which normally is costly and complicated but offers its HQ full control. This mode is more suitable for those industries that directly communicate with end customers, require high level of skills, specialty, especial know-how and customisation (Hitt, 2009). Greenfield investment is more effective to build physical and high cost plants. It is widely used by MNCs to engage in those markets where have no competitors to purchase or transfer competitive advantages that include embedded competencies, skills and culture (Szalucka, 2010).

Meanwhile, acquisition as a form of FDI helps MNCs to fast enter foreign markets. By acquisition, MNCs can fast grasp market power which brings better market power. To fast expand into a foreign country, MNCs generally acquire a competitor, supplier, distributor or a company engaging in a related industry to grow their core competency and then competitive advantage in the country (Szalucka, 2010). However, acquisition faces the following disadvantages: 1) the difficulties in integrating two companies due to differences in organisational culture, management system; 2) the increase in debt level of a company due to acquisition; and 3) diversification issues caused by the acquisition (Hennart and Park, 1993).

To be noticed, many developing countries offer attractive policies to inbound FDIs because they can transfer knowledge, develop labours and bring job opportunities (Khan and Akbar, 2013). For example, Thai government has advantages in terms of FDI restrictions. In other words, it has weaker and fewer FDI restrictions comparing to Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam (Macek et al., 2015). Meanwhile, Thai government offers investment consultancy services, post-investment services and accelerates the process of applications and permits (Macek et al., 2015).

2.4 Entry Barriers

Karakaya and Stahl (1993) summarise the entry barriers to developing countries, including government policy, product differentiation/adaptation, culture difference, distribution channels, customer service, competition, currency exchange, buyers’ switching costs and market experience and knowledge in a host country. Product differentiation/adaptation and market experience & knowledge are related with cross-culture issues. Political issue is the most important entry barrier to MNCs to gain a successful expansion in a developing country (Khan and Akbar, 2013). They have to face political instabilities, uncertain and ambiguous policies, overmuch government interference and paternalism in Asian countries (He, 2010). Changes in political environment can be frequent and significant that have strong influences on a MNC’s operation and strategy (Khan and Akbar, 2013). Furthermore, developing countries tend to have unwritten regulations and policies that are hard for MNCs to understand. Therefore, developing government relation is critical for MNCs to relieve political risks. Furthermore, MNCs have to face Intellectual Property (IP) protection issues in developing countries where generally have a weak IP protection (Hossain and Lasker, 2012).

Meanwhile, MNCs need to develop distribution channel and acquire market knowledge in a host country, which is associated with Uppsala model. By cultivating business network, they can build distribution channel and absorb market knowledge.

2.5 Global Value Chain and Value Chain

With the rise of globalisation, many developing countries have engaged in global value chain while most of them offer low-valuing adding services because they have less expertise and speciality in high-valuing adding services such as R&D, marketing (branding), etc. (McDermott and Corredoira, 2010). Developing countries have low labour costs and have advantages in taking high pollutive and intensive labour manufacturing works (McDermott and Corredoira, 2010). In return, developing countries expect to absorb knowledge from MNCs and develop their labour force in long-term (Morrison et al., 2008). MNCs however seek the lowest costs when they develop their value chain activities in developing countries (Giuliani et al., 2017).

Furthermore, Porter’s value chain categorises a company’s activities into two groups: 1) primary activities (inbound/outbound logistics, operations, marketing & sales and service); and 2) support activities (firm infrastructure, HRM, technology and procurement) (Porter, 1985). An MNC needs to consider its value chain when it develops its internationalisation strategy (Barnes, 2001).

Figure 3: Porter’s value chain (Source from: Porter, 1985)

3.0 Internationalisation Process of H-D

3.1 The History of HD’s Overseas Investment

H-D was founded in 1903 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Only 9 years after its establishment, the company started to export its motorcycles to Japan which is its first foreign market. In the 1910s, the trade between Japan and the US was especially prosperous, and American products had more competitive advantages in Japan than other developed countries such as Germany, the UK, etc. Thus, H-D firstly entered Japan in 1912.

Since 1912, H-D begun to develop its dealer network around the world. During the World War I, H-D supplied the US Army which used 20,000 its motorcycles and spread them around the world. This helped H-D to foster its global reputations and spread its products around the world. In 1920, H-D was sold to 67 countries around the world by 2,000 dealers. It sold its products to Canada that was close to the US, to the UK which had a similar culture with the US. In 1935, H-D licensed its blueprints, dies and machinery to a Japanese company known as the Sankyo, which found the Rikuo motorcycle (Harley-Davison, 2020). H-D expanded into these countries by dealership, which could be regarded as exporting via agency.

The first overseas factory of H-D is located in Manaus, Brazil, built in 1998. H-D entered Hong Kong in 1995 and authorised its first dealer in Beijing, China in 2006 (Sui, 2006).

In 2009, H-D planned to expand into India and begun to market its products in 2010.

3.2 Overseas Affiliates

The internationalisation process of H-D accords with Uppsala model. Its internationalisation started with exporting via agency (dealership), shifted to joint venture, moved to leased manufacturing facilities and finally switched to wholly owned manufactures.

3.2.1 Export via Agency (Dealership)

H-D has expanded into 67 countries by 1935 by taking advantage of dealership. This can be viewed as exporting via agency. H-D’s dealership acted as the role of exporting agency and sales representatives. These sales representatives represent H-D in their local markets for H-D’s products on sales. They offer H-D supports including local advertising, local sales presentations, solution of legal issues, distribution, retailing, and after-sales services. This tactic allowed H-D to expand into many countries in a fast and effective way. Also, the company developed global brand equity including awareness and image, fostered its business networks and accumulated business experience. More importantly, with this tactic, H-D avoided large scale of investment and high risks potentially caused by intensive internationalisation. By dealership, H-D did not need to invest in its presences in host countries and endure the political and investment risks. In terms of Uppsala model, the company started with export via exporting as its first entry mode in its original process of internationalisation because it lacked market knowledge and business networks in host countries.

3.2.2 Joint Venture Model

After decade’s growth, H-D gradually moved to the ‘joint venture model’. This means that the company built joint ventures with local companies for marketing activities and distribution in a host country. These joint ventures helped H-D to develop proper level of localisation, facilitate its local distribution and share political risks and monetary risks. The joint venture model allowed H-D to take advantage of its partners’ market power, size, and resources and enjoy their business networks in host countries to facilitate distribution and government relations. However, the partners are unlikely to acquire technologies from H-D because they only take responsibility of distribution tasks. Thus, this model avoids H-D to lose its Intellectual Properties (IPs), knowhow and commercial secrets. The company used the model in North America at first and in Europe because countries in these continents have been culturally close to the US. Thus, the cultural clashes caused by the joint ventures between H-D and local companies were relatively small. This relieved H-D’s pressure to solve cross-cultural issues. Then, the joint venture was implemented gradually to those countries which were culturally and economically far from the US.

In terms of Uppsala model, H-D gradually increased its involvement and commitment in foreign markets by leasing manufacturing facilities in a host country. Since 1993, H-D started to sell its motorcycles in Brazil. After 5-years’ operation in the country, the company accumulated some market knowledge and developed a certain level of business networks. With its declining sales performance in the US, H-D as a seeker of new markets and networks was motivated to increase sales performance and profitability and develop a manufacturing plant for the whole South American market. H-D established its first overseas factory in Manaus, Brazil to gain benefits from the country’s free economic zone in 1998 (Bizjournal, 1998). The factory in the country was for South American markets. The factory was in free-trade zone for motorcycle productions, which allowed the company to bypass tariffs so as to facilitate its sales in South America. Given that H-D did not have sufficient experience of operating a manufacturing facilities and sound business networks in Brazil in 1998, the company chose joint venture as entry mode by collaborating with a Brazilian company known as Paulo Izzo. However, H-D has been the major stakeholders of the venture, which allowed it to protect its important IPs, knowhow, and knowledge in a proper way. Additionally, South America has been culturally and geographically close to the US, which caused relatively smaller and fewer cross-cultural issues to H-D. In early 2011, H-D further expanded its scales in the country by adding more distributors (Dumitrache, 2010). In terms of Uppsala model, this expansion was based on the increased H-D’s business networks and market knowledge in Brazil. Between 1993 and 2011, the company has been growing its business network and market knowledge, which allowed it to further expand its business networks. Meanwhile, the expansion also was motivated by slow sales growth of H-D in the US. The company expected to increase its profitability by more intensive internationalisation.

Based on the experience in Brazil, H-D was able to build its manufacturing facilities in those countries which have been culturally and geographically far from the US in accordance with Uppsala model. H-D built a subsidiary in Gurgaon, India and developed the host country’s deal network in 2011, one year after it started to sell its motorcycles in the country and two years after its announcement of its expansion plan (RP News Wires, 2016). The company expected to explore the tremendous potential of the Indian motorcycle market and facilitate its globalisation process. It regarded as expansion in India as a part of its globalisation strategies and an important step to expand into Asia (Triwastuti, 2017). After 3 years’ operation, H-D accumulated market knowledge and developed its business network, which enabled it to operate its manufacturing facilities in India. In 2014, H-D started to manufacture its less-heavy motorcycles (the Street 750 and 500) at Bawal, Haryana India (RP News Wires, 2014). These products have been H-D’s basic products with 750 cc emission load and 500 cc emission load. Also, the platform of the Street 750 was manufactured jointly by H-D’s American factory and Indian factory. It means that H-D’s Indian plants did not take responsibility for manufacturing important products. H-D’s still focused on its plants in the US.

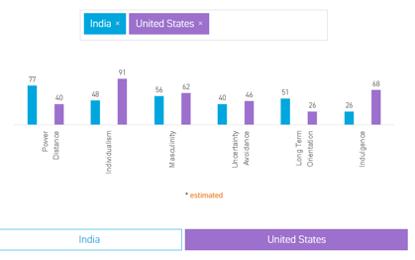

More importantly, H-D overcame the two critical issues in India, including political uncertainty and cross-cultural issue. The differences in political environment between the US and India have been large. With a developing economy, Indian government was likely to frequently change policies and offered a low degree of economic freedom (Triwastuti, 2017). To address political uncertainty, H-D obtained the supports from the US government. In 2007, The US Trade Representative signed an agreement with the Minister for Commerce and Industry of India, which allowed the entry of H-D in exchange of Indian mangoes (Business Line, 2011). Thus, this means that H-D’s expansion was supported by both the US government and Indian government with the trade agreement which relieved political risks. Another challenge was cultural differences between the two countries. In terms of Hofstede’s national cultural dimensions, they are diverged in power distance, individualism, long-term orientation, and indulgence, as figure 3 shows (Hofstede-Insights, 2020).

Figure 4: India and the United States

(Source from: Hofstede-Insights, 2020)

H-D had to solve the problems resulted from individualism (Triwastuti, 2017). With a collectivistic culture, Indian people tended to avoid conflicts, openness, and positive confrontation for solutions, whereas Americans with a highly individualistic culture are more likely to debate and talk aggressive languages (Triwastuti, 2017). Meanwhile, under high power distance, Indian employees have been unlikely to participate into decision-making and have autonomy. However, American employees have been on the opposite side. Also, H-D used matrix organisational structure which furtherly slowed down its decision-making process. To solve cultural issues, H-D hired the CEO who understood both Indian and American culture and was born in Indian family but grew-up, learned and worked in the US (Triwastuti, 2017).

According to Triwastuti (2017), the convergence in masculinity and uncertainty avoidance between Indian and American culture enables H-D to drive its Indian employees by competition, achievement, and success. H-D has been using these in the US. In this sense, H-D did not need to develop new strategies and techniques to motivate Indian employee.

By partnership in Brazil and India, H-D absorbed market experience and knowledge about the two countries from its partners and developed its business networks in there, which are consistent with Uppsala model. By these business networks, the company was allowed to further exploit Southern American market and Asian market.

3.2.3 Wholly Owned Subsidiaries

The Brazilian and Indian expansions helped H-D learn and accumulate knowhow and knowledge for internationalisation. Also, the company learned how to operate in Asia which is culturally and geographically far from the US by operating in India. This was critical for H-D to build wholly owned plants in Thailand in accordance with Uppsala Model.

By 2019, H-D operated manufacturing facilities in three foreign countries including Thailand, Brazil, and India. However, it only fully owns its manufacturing facilities in Thailand. According to Harley Davison (2020), H-D has five subsidiaries in Thailand, including Harley-Davison (Thailand) Company Limited, HDMC (Thailand) Ltd., H-D Motor (Thailand) Limited, and H-D Motorcycle (Thailand) Limited. These subsidiaries take responsibilities of manufacturing as well as sales in the country and exporting to other countries. These subsidiaries are wholly owned by H-D. On the other hand, its manufacturing facilities in Brazil and India are leased (Harley Davison, 2019). This means that H-D increased its involvement in its international market, with the growth of its internationalisation experience.

More importantly, with the growth of its international presence, H-D gradually switched its focus from the US to its international market. H-D has been paying increasingly more attention to its overseas plants. Its plants in Brazil and India have been manufacturing its low-end products and its major manufacturing relied on its American factories before its Thai plants. H-D closed two of its important factories in the US and planned to gradually move most of its manufacturing facilities to Thailand. The whole internationalisation process of H-D has been strictly complying with Uppsala Model. It started with export via agency, moved to joint venture and partially owned manufacturing in Brazil and India, and wholly owned manufacturing facilities in Thailand. Also, H-D expanded into Brazil which has been culturally and geographically close to the US and then into India which has been culturally and geographically far from the US.

The market potential of Thailand is not huge whereas H-D’s presence in the country allows the company to improve its efficiency and network in Asian market. H-D uses its Thai manufacturing plants as its base to export its products to all Asian countries especially China. These plants allow the company to bypass high tariffs of China and other Asian countries. Meanwhile, H-D can reduce its logistics distance and thus diminish down costs and improve efficiency.

3.2.4 Motives of H-D’s Internationalisation

The most significant motive of H-D was market-seeking. The US market was mature and growing slowly, which forced the company to explore foreign markets. During 2002-2008, H-D climbed to 50% share of heavyweight motorcycle and became a firm market leader in the US (Checkcapital, 2008). Meanwhile, the 2008 Financial Crisis sharply reduced H-D’s sales performance by 13.1% and its profits by about 30% (Gray, 2008). This decline was caused by the decreased consumption confidence and capabilities and demands. The Financial Crisis caused the decrease in disposable income (Triwastuti, 2017). Thus, H-D had to explore international opportunities and reach more customers in overseas.

Secondly, H-D was motivated to use the cheap labour forces in Brazil, India, and Thailand. This can be viewed as resource-seeking in accordance with Dunning (1993)’s argument. These countries had much lower labour cost than the US. Also, the environment protection laws and enforcement in these countries have been much looser than the US. Based on the pollution haven theory, H-D has been facing lower environmental costs in these countries and thus improving profitability. Generally, these expansions allowed H-D to reduce costs (labour costs, environment costs, and tariffs) so as to improve profitability. To be noticed, profitability and sales volume have been two critical problems for H-D. Thus, it has been using internationalisation to solve the two problems.

Moreover, the third motive was network-seeking and efficiency seeking. By building manufacturing plants, H-D can bypass high tariffs and facilitate its growth and internationalisation. Triwastuti (2017) points out that the expansion into India was motivated by seeking efficiency. India has been an important base of international offshoring and the expansion allowed H-D to facilitate its internationalisation. The products manufactured in India have been supplied to India and international market (Business Line, 2011).

Furthermore, H-D was motivated by its competitors’ intensive internationalisation process. For example, BWM and Japanese motorcycle brands including Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki as major manufacturers of heavy motorcycles also were increasing their commitment and involvement in Asian market. Asian market has been the major market of those Japanese motorcycle brands which built their plants in Thailand to reduce costs. Ducati as another rivalry of H-D planned to build manufacturing facilities in Thailand in 2011 to improve its presence and networks in Asia (Frank, 2011). Based on Dunning (2000)’s theory, the competitors of H-D increased their commitment and involvement in Asian market, which rose H-D’s motive to penetrate Asian market.

4.0 Case Study

4.1 Rationale, Activities, Position in value-chain, Prior Exports

4.1.1 Motives of Entering Thailand

4.1.1.1 External motives

By expanding into Thailand, H-D can bypass the high tariffs of Chinese government so as to increase its sales performance and expand its business in China and other ASEAN countries. H-D has been constricted by the trade barriers of China to increase its sales in the country since it entered to there in 2006 (Sui, 2006). Chinese government charge high tariffs, consumption tax, and Value Add Tax (VAT) to H-D’s products (Sui, 2006). For powerful motorcycles, Chinese government charge higher tax. For instance, it imposes 30% tariff, 17% consumption tax and 10% VAT (a 69.0% composite tax rate) on those imposed motorcycles with over 800cc (engine discharge). However, almost all motorcycles of H-D have an engine discharge larger than 800cc. Moreover, the US and Chinese government engaged in the trade war and the antagonism between the two countries tended to be increasingly more intensive. Chinese government announced to add 25% tariffs imposed on all imported good manufactured from the US (Bekkers, 2020). This certainly intensified H-D’s commitment to expand into Thailand. China has a Free Trade Agreement with (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) ASEAN, known as the ACFTA, covering 10 members of the ASEAN including Thailand. China was first one who proposed the idea of a free trade area in 2000 (ASEAN, 2015). In 2010, the average tariff rate on ASEAN products imposed by China dropped from 9.8% to 0.1% (ASEAN, 2015). Thus, H-D can take advantage of the ACFTA agreement by building manufacturing facilities in Thailand to bypass the high tariff imposed by Chinese government. This motive of H-D can be explained by efficiency seeker in Dunning (1993)’s argument because the expansion of H-D in Thailand can reduce tariffs of all members of the ACFTA including China. Meanwhile, the expansion can reduce the efficiency of logistics by reducing logistics distance to all Asian markets so as to reduce costs and responsiveness demands.

Furthermore, H-D found the rising demands in Southeast and East Asia. Thus, it has been committing to build manufacturing facilities in Thailand to grasp the rising demands (Reuters, 2017). By these facilities, H-D can enhance its responsiveness and competitiveness in Asia and China. The manufacturing facilities can diminish down the prices thus gaining competitive advantage and attracting more customers. H-D adopts it to increase its presence in Asia-Pacific market. More importantly, H-D recognised that it has competitive advantages including global brand image, heritage and differentiated products in Asian market. The company can represent American culture and the value of freedom. This motive of H-D is consistent with market-seeker in Dunning (1993)’s theory. H-D predicts that the company can increase sales performance and profits in Asian market.

Additionally, H-D can enjoy lower labour costs and loose environmental law enforcement in Thailand to reduce costs. The minimum wage in the country was only US$ 10.57 per day (Trading Economics, 2020). This is consistent with pollution haven theory (Levinson and Taylor, 2008) and the motive of resource-seeking (Oviatt and McDougall, 2005).

4.1.1.2 Internal motives

The rationale of this international expansion is related with internal environment of the H-D. The company has been suffering declining demands in its domestic and traditional markets such as Europe. Its domestic sales have been declining since 2010 mainly because young Americans are less inclined to riding. It has been hard for the company to reach and affect younger markets especially millennials (Rozsa, 2018). According to H-D’s annual report in 2018 (Harley Davison, 2019), the company’s total revenue shows a decreasing trend between 2018 and 2014, from US$ 6,228.5 million in 2014 to US$ 5,716.9 million in 2018. H-D has to explore new markets to ensure its sustainability and cover the declining traditional markets. Thus, the expansion in Thailand is consistent with the argument of Dunning (2000) and Yip et al. (2000): H-D suffered a saturated market and had to explore new market for growth and sustainability.

4.2 Global Value Chain and Value Chain

H-D’s expansion fits in global value chain theory (McDermott and Corredoira, 2010). The company moved its manufacturing facilities to the developing country (Thailand) where offers low-valuing adding services because they have less expertise and speciality in high-valuing adding services such as R&D, marketing (branding), etc. More importantly, Thailand has low labour costs and have advantages in taking high pollutive and intensive labour manufacturing works, which also is consistent with McDermott and Corredoira (2010)’s argument. In details, the country has a large number of skilled labours for automobile manufacturing because many automobile manufacturers have largely invested in the country to build plants and train skilled labours, including car manufacturers such as Toyota, Ford and motorcycle manufacturers such as Honda, Ducati, Yamaha, Kawasaki, Suzuki and BMW (Business Wire, 2018). Therefore, H-D can enjoy low and skilled labour in the country and optimise its value chain.

In accordance with Porter’s value chain theory (Porter, 1985), the company can optimise its primary activities including inbound/outbound logistics and operations. As mentioned, its Thai manufacturing facilities can reduce logistics distance to Asian countries and use ASEAN agreement to enjoy fast pass of the customers and lower tariffs.

However, H-D tends to face HRM issues in Thailand. According to the arguments of Antunes et al. (2013) and Beguelsdijk et al. (2017), H-D has to address the differences between Thai employees and American expatriates in terms of value, opinion, attitude, perception and communication styles and may face misunderstanding, ineffective communication and conflicts. The company has collected sufficient market knowledge and developed sound cultural capabilities for Asia when it has been operating its Indian plants and its distribution networks in Thailand. Based on Uppsala model, the company can effectively address these cross-cultural issues.

4.3 Entry Mode

HD adopted FDI to involve into Thailand this because it has collected enough experience and developed sufficient cultural capabilities in Asia, which is consistent with OLI theory. The company has operational, locational and internalisation advantages.

Under FDI, H-D used green investment as its entry mode to build its own manufacturing facilities. Given that these facilities are critical for H-D’s growth in Asia and sustainability, it is suitable for the company to adopt greenfield investment. In accordance with Hitt (2009)’s argument, green investment allows H-D to establish a wholly owned subsidiary and to fully control it. This means that the company can strictly control quality, manufacturing process, production schedule and output to effectively response Asian market. By controlling production, the company can achieve high level of Just-In-Time (JIT) manufacturing to improve efficiency, reduce oversupplies and control costs. By controlling product quality, it can ensure its global brand image and competitive advantages. Also, manufacturing H-D’s products requires relatively high skills and the company can transfer these skills by green investment. Hitt (2009) highlights that greenfield investment is more effective to build physical and high cost plants. To be noticed, these plants of H-D are costly. In accordance with Szalucka (2010)’s argument, H-D can transfer competitive advantages that include embedded competencies, skills and culture to its Thailand plants by green investment.

4.4 Partners in this International Expansion

H-D did not reveal any strategic partners in Thailand because it has been focusing on building its wholly owned subsidiary and facilitating its new distribution network in the country. However, its Thai plant can be viewed as the start of exploring Asian market. The company announced its strategic partnership with Qianjiang to develop a 338cc motorcycle especially for Asian market (Blain, 2019). The partnership allows H-D to further understand Asian customers’ needs and wants and acquire market knowledge, which accords with Uppsala model.

More importantly, the partnership helps H-D to achieve high level of localisation to meet local customers’ needs and wants, which is supported by the arguments of Antunes et al. (2013). Asian customers have different demands for motorcycle due to their culture, environment, traffic condition and consumption capability. They have preferences to smaller and more convenient motorcycles with less fuel consumption (Blain, 2019). The usage costs are price of the 338cc motorcycle are more economical and affordable to Asian consumers. Thus, the company achieves high level of localisation and responsiveness to Asian market and develops its business network by the partnership. In Uppsala model, this partnership allows H-D to increase its market commitment and involvement in Asia market.

4.5 Strategic Fit

The expansion of H-D in Thailand highly strategically fits in its overall internationalisation strategy. The company has strategic objective to develop emerging markets especially in Asia (Harley Davison, 2019). It has great commitment to internationalisation. It has the vision to develop younger generation of riding throughout the world (Harley Davison, 2019). By engaging in Asia, the company certainly can cultivate younger generation of Asian riders, develop customer relationship and loyalty. Furthermore, the company’s strategy focuses on global expansion and exploration of international market to cover the declining US market. The partnership with Qianjiang to build the 338cc motorcycle is consistent with H-D’s strategic objective of developing new products to expand into new markets and segments (Harley Davison, 2019).

According to Harley Davidson (2020b), the company has the objectives: to reduce cost structure, to reduce SKUs and to focus on Asia Pacific. Its Thai plants can reduce costs, improve JIT manufacturing to reduce SUKs and increase its presence in Asia Pacific.

4.6 Overcoming Entry barriers

The major entry barriers retrieved from political challenges, whereas the US government arose these challenges rather than Thai government. The Trump administration encouraged US-based MNCs to move back their plants to USA so as to bring jobs back to Americans. The government made many efforts to accomplish the objective of bringing jobs back to the US, including tax reduction, monetary incentives and loan benefits (White House, 2017). However, H-D announced its plan to gradually shut down its American plants and bring jobs to Thailand. The US President Trump conspicuously advocated boycott H-D resulting in declines in its sales (Rozsa, 2018). However, H-D endured the political pressure and continued its Thai project.

Thai government has very few restrictions on FDI. According to Thai Government (2020), many local restrictions on FDI were abolished. There is no special restriction on FDI in automobile manufacturing industry. Instead, FDI may receive tax privileges and non-tax incentives. Since 1993, Thai government has permitted 100% foreign ownership of automobile assembly plant (Thai Government, 2020). This means that H-D is allowed to use green investment to build wholly owned subsidiary.

H-D had its own dealership network and distribution network in Thailand before its factory project. This means that it solved the distribution barrier in Karakaya and Stahl (1993)’s argument. Furthermore, the company has been collecting cultural knowledge and developing cultural capabilities, so it can effectively address culture differences. Nevertheless, there are still some entry barriers to H-D. H-D still faces product adaptation issues because it offers standardised products to Asian market. To solve this issue, the company built a partnership with Qianjiang to develop localised products.

In accordance with Hossain and Lasker (2012)’s argument, H-D has to address weak IP protection issues in Thailand. The green investment in Thailand allows H-D to relieve the IP protection issues in Thailand. By green investment, the company can avoid the leak of its IPs to its joint venture partners.

Even though H-D’s green investment cannot largely reduce political risks and improve government relation like joint venture with local company, the company has long operating experience and sufficient network in the country. Its previous operating experience allows it to properly address government relations and political issues.

5.0 Conclusions

H-D uses its Thai plants as a breaking point to largely and fast expand in Asia by taking advantage of lower prices and higher level of localisation. The most interesting fact is that H-D had to confront with the US government to realise its Thai expansion. This research finds that H-D’s internationalisation process fits Uppsala model. Its internationalisation started with exporting via agency (dealership), shifted to joint venture, moved to leased manufacturing facilities and finally switched to wholly owned manufactures. To build local factory, H-D started with Brazil which is geographically and culturally close to USA and then gradually engage in India and Thailand which are geographically and culturally far with USA. Furthermore, this research finds that HD’ Thai expansion fits its overall internationalisation strategy. More importantly, the company has been developing its capabilities and knowledge for internationalisation. It has enough understanding on Asian culture to solve cultural barriers.

Moreover, H-D has the following motives to develop manufacturing facilities in Thailand, including lower labour costs, more natural resources, and loosen enforcement of environmental and labour laws. Thus, it seeks resources, market, efficiency and networks. Furthermore, H-D was motivated by its competitors’ intensive internationalisation process. Also, it has to exploit international market to cover its declining revenue in domestic market so as to ensure its sustainability. The market potential of Thailand is not huge whereas H-D’s presence in the country allows the company to improve its efficiency and network in Asian market. H-D uses its Thai manufacturing plants as its base to export its products to all Asian countries especially China. By building manufacturing facilities in Thailand, the company can bypass China’s high tariffs thus improving its competitive advantages and reducing costs in the country.

With its operational capabilities, the company has locational, operational and internationalisation advantages. Thus, it used green investment as its entry mode to build its own manufacturing facilities. Green investment allows H-D to strictly control quality, manufacturing process, production schedule and output to effectively response Asian market.

H-D’s expansion fits in global value chain theory. The company moved its manufacturing facilities to the developing country (Thailand) where offers low valuing adding services with low labour costs and skilled labour.

More importantly, the strategic fit of the expansion is high. H-D can achieve high level of localisation and responsiveness to Asian market and develops its business network by its partnership with Qianjiang. The partnership that builds the 338cc motorcycle is consistent with H-D’s strategic objective of developing new products to expand into new markets and segments.

This research predicts that H-D can have a great prospect in Asia because its expansion in Thailand and Asia fit internationalisation theories and its own strategy. It has sound experience and cultural capabilities and great commitment to localisation. Its partnership with Qiangjiang will be effective because it has efficient cultural capabilities. More importantly, its localisation strategy can bring more new customers and cultivate more younger riders. By lower costs and localised products, the company can gain higher customer satisfaction and meet more demands thus achieving growth in Asia. However, it also needs to address the inconsistencies in its brand image. Given that H-D has been making heavy motorcycles (at least 750 cc), the 338cc product may compromise H-D’s tough brand image throughout the world.

Reference

Antunes, I., Barandas-Karl, H., & Martins, F. V. (2013). The impact of national cultures on international marketing strategy and subsidiary performance of Portuguese SME’s. The International Journal of Management, 2(3), 38-45

ASEAN (2015) ‘ASEAN-China Free Trade Area - Building Strong Economic Partnerships’, [online] Available at: < https://www.asean.org/storage/images/2015/October/outreach-document/Edited%20ACFTA.pdf>. [Accessed on 22 July 2020]

Barnes, S. J. (2001). ‘The mobile commerce value chain: analysis and future developments’, International Journal of Information Management, 22 (2): 91–108.

Beguelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., Kunst, V. E. et al. (2017) Cultural Distance and Firm Internationalization: A Meta-Analytical Review and Theoretical Implications, Journal of Management, 44(1), 89-130

Bekkers, E. (2020). ‘An Economic Analysis of the US-China Trade Conflict’, [online] Available at: < https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd202004_e.pdf>. [Accessed on 22 July 2020]

Birdsall, N. and David, W. (1993). Trade Policy and Industrial Pollution in Latin America: Where Are the Pollution Havens? The Journal of Environment & Development. 2 (1): 137–149

Bizjournal (1998) ‘Harley to assemble motorcycles in Brazil’, [online] Available at:

Blomstermo, A. and Sharma, D. D. (2003). Learning in the internationalisation process of firms. Edward Elgar. pp. 36–53

Boyacigiller, N. (1990). The role of expatriates in the management of interdependence, complexity and risk in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(3): 357–381,

Business Line (2011) India will export mangoes, import motorbikes from US, [online] Available at: <https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/todays-paper/India-will-export-mangoes-import-motorbikes-from-US/article20161440.ece >. [Accessed on 22 August 2020]

Business Wire (2018) ‘Thailand Automobile Manufacturing Industry Report 2018-2022 - Production to Exceed to 2.4 Million Units’, [online] Available at:

Blain, L. (2019) Harley-Davidson partners with Qianjiang to produce a 338cc hog for Asia, [online] Available at: < https://newatlas.com/chinese-harley-davidson-qianjiang-china/60225/>. [Accessed on 22 August 2020]

Calof J.L. & Beamish P.W. (1995). Adapting to Foreign Markets: Explaining Internationalization, International Business Review, 4(2): 115-1

Checkcapital. (2008). Harley-Davidson: research report, [online] Available at:

Chen, Tain-Jy, Chen, Homin and Ku, Ying-Hua (2004). Foreign direct investments and local linkages. Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 35: 4, pp. 320-333.

Ciszewska-Mlinaric, M. and Trapczyniski, P. (2016). The Psychic Distance Concept: A Review of 25 Years of Research (1990-2015), Journal of Management and Business Administration Central Europe, 24(2), 2-31.

Darley, W. K., Luethge, D. J., and Blankson, C. (2013). Culture and international marketing: A sub-Saharan African context. Journal of Global Marketing, 26(4), 188-202

Dumitrache, A. (2010) ‘Harley-Davidson Plans Network Expansion in Brazil’, [online] Available at: < https://www.autoevolution.com/news/harley-davidson-plans-network-expansion-in-brazil-27518.html>. [Accessed on 1 August 2020]

Dunning, J. H. (1993). Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy. Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

Dunning, J. H. (2000). The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. International Business Review, 9(2), 163-190.

Ekerete, P. P. (2001). The effect of culture on marketing strategies of multinational firms: A survey of selected multi-national corporations in Nigeria. African Study Monographs, 22(2), 93-101

Evans, J. and Mavondo, F. (2002). ‘Psychic Distance and Organizational Performance: An Empirical Examination of International Retailing Operations’. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3): 515–532,

Forsgren, M. (2015). ‘The Concept of Learning in the Uppsala Internationalization Process Model: A Critical Review, Knowledge’, Networks and Power, pp. 88 – 110.

Frank, A. (2011) Do you really know where your bike was built, [online] Available at: < https://www.motorcyclistonline.com/do-you-really-know-where-your-bike-was-built/>, [Accessed on 3 August 2020].

Giuliani, E., Marchi, D. V. and Rabellotti, R. (2017). ‘Do Global Value Chains Offer Developing Countries Learning and Innovation Opportunities?’ European Journal of Development Research, 1-14

Gray, S. (2008). Harley-Davidson tries to rejuvenate its business, Times Magazine Online, [online] Available at:

Harris, S. and Wheeler, C. (2005). Entrepreneurs’ relationships for internationalization: functions, origins and strategies. International Business Review, vol. 14, pp. 187–207.

Harley Davidson (2019) ‘Harley Davidson, Inc.’ [online] Available at: < https://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReportArchive/h/NYSE_HOG_2018.pdf>. [Accessed on 10 July 2020]

Harley Davidson (2020). Get the Rest of The Story, [online] Available at: < https://www.harley-davidson.com/us/en/museum/explore/hd-timeline.html>. [Accessed on 10 July 2020]

Harley Davidson (2020b) ‘Our Strategy’, [online] Available at:

He, B. (2010). Four Models of the Relationship between Confucianism and Democracy. Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 37, 18-33.

Hennart, J.F. and Park, Y. R. (1993) Greenfield vs. Acquisition: The Strategy of Japanese Investors in the United States, Management Science, 39 (9), 1054-1070

Hitt, A. (2009) Strategic Management Competitiveness and Globalization, Nelson Education Ltd

Hofstede-Insights (2020) ‘Country Comparison, India and United States’, [online] Available at: <https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/india,the-usa/ >. [Accessed on 11 July 2020]

Hollensen S. (2007). Global marketing, 4th edition, Pearson Education Limited, pp 63

Hossain, A. and Lasker, S. (2012). Intellectual Property Rights And Developing Countries, Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics 1(3), 43-46

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). ‘The internationalization process of the firm – a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments’. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1): 23–32

Johanson, J., and Vahlne, J-E. (1990). The Mechanism of Internationalization. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International.

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). ‘The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership’. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9): 1411–1431,

Khan, M. M. and Akbar, M. (2013) The Impact of Political Risk on Foreign Direct Investment, International Journal of Economics and Finance 5(8), 132 - 147

Karakaya, F. and Stahl, M. J. (1993) Global Barriers to Market Entry for Developing Country Businesses, Proceedings of the 1993 World Marketing Congress, pp. 208-212

Kingsley, G. & Malecki, E. J. (2004). Networking for Competitiveness. Small Business Economics, vol. 23, pp. 71–84.

Lavie, D. (2006). The Competitive Advantage of Interconnected Firms: an Extension of the Resource-Based View. Academy of Management Review, vol. 31: 3, pp. 638–658.

Levinson, A., M. and Taylor, S. (2008). "Unmasking the Pollution Haven Effect" (PDF). International Economic Review. 49 (1): 223–54.

Macke, A., Bobek, V., and Vukasovic, T. (2015). Foreign direct investment as a driver of economic development in Thailand, Journal of International Business Studies, 8(2), 49-74.

McDermott, G.A., and Corredoira, R.A. (2010) 'Network composition, collaborative ties, and upgrading in emerging-market firms: Lessons from the Argentine autoparts sector’, Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2): 308-329

Morrison, A., Pietrobelli, C., and Rabellotti, R. (2008) ‘Global value chains and technological capabilities: A framework to study industrial innovation in developing countries’, Oxford Development Studies 36(1): 39–58.

O’Grady, S. and Lane, H.W. (1996). The psychic distance paradox. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(2): 309–333,

Oviatt, B. M. and McDougall, P. P. (2005). Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 36, pp. 29–41.

Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. The Free Press

Rao-Nicholson, R., and Khan, Z. (2016). Standardization versus adaption of global marketing strategies in emerging market cross-border acquisitions. International Marketing Review, 34(1), 138-158.

Reuters (2017) ‘Harley-Davidson plans Thailand factory to serve Southeast Asian market’, [online] Available at: < https://www.cnbc.com/2017/05/25/harley-davidson-plans-thailand-factory-to-serve-southeast-asian-market.html>. [Accessed on 20 May 2020]

Rozsa, M. (2018) ‘Harley Davidson sales suffer worst decline in 8 years following Trump's calls for a boycott’, [online] Available:

RP News Wires (2014) ‘Harley-Davidson to launch assembly operations in India’, [online] Available: < https://www.reliableplant.com/Read/27289/Harley-Davidson-assembly-India>. [Accessed on 11 June 2020]

RP News Wires (2016) ‘Harley-Davidson announces plans to expand into India’, [online] Available: <https://www.reliableplant.com/Read/19717/harley-davidson-announces-plans-to-exp-into-india#:~:text=Harley%2DDavidson%20Inc.,the%20process%20of%20seeking%20dealers. >. [Accessed on 11 June 2020]

Ryans, J.K., Griffith, D.A., and White, D.S. (2003) ‘‘Standardization/adaptation of international marketing strategy. Necessary Conditions for The Advancement of Knowledge”, International Marketing Review, Vol. 20 No. 6, pp. 588-603.

Schuyler, D. (2019) ‘Harley-Davidson ends production at Kansas City plant’, [online] Available at: < https://www.bizjournals.com/milwaukee/news/2019/05/28/harley-davidson-ends-production-at-kansas-city.html >. [Accessed on 20 May 2020]

Sui, C. (2006) ‘Harley-Davidson Roars Into China’, [online] Available at:

Szalucka, M. (2010). Acquisition Versus Greenfield Investment – the Impact on the Competitiveness of Polish Companies, Journal of Business Management, 3, 5-10.

Thai Government (2020). Foreign Direct Investment, [online] Available at: < https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:FaiFCpkb8B8J:https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx%3Ffilename%3DQ:/WT/TPR/S9-3.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us>, [Accessed on 24 August 2020]

Triwastuti, R. (2017) Market Entry Strategy of Multinational Enterprise (MNE): A Case Study of Harley Davidson, The International Journal of Applied Business, 1(2), 40 - 51

Yeoh, P. (2000). Information Acquisition Activities: a Study of Global Star-up Exporting Companies. Journal of International Marketing, vol. 8: 3, pp. 36-60.

Yip, G. S., Biscarri, J. G. and Joseph A., M. (2000). The Role of the Internationalization Process in the Performance of Newly Internationalizing Firms. Journal of International Marketing, vol. 8: 3, pp. 10-35.

White House (2017) ‘Remarks by President Trump in Meeting with Manufacturing CEOs’, [online] Available at: < https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-meeting-manufacturing-ceos/>, [Accessed on 20 August 2020]

English

English Chinese

Chinese